Lessons from Shake Shack Founder Danny Meyer, with a Side of Fries

Next time you get ready to inhale a ShackBurger at Shake Shack, the American fast-food chain with restaurants across the U.S. and internationally in countries like China and Qatar, remember this. Founder Danny Meyer’s Shake Shack meal of choice is a plain cheeseburger, fries and a coffee milkshake. His all-time favorite meal anywhere? Sausage and mushroom pizza.

A foodie since he was a boy, Meyer launched his career as a restaurateur in 1985 at age 27, building an upscale, fine-dining empire with top New York City restaurants like Union Square Café and Gramercy Tavern. He is currently executive chairman of the Union Square Hospitality Group, which owns several restaurants.

Along the way, Meyer decided to bring his special brand of hospitality to the fast-food industry, launching Shake Shack as a humble hot dog cart inside Madison Square Park in New York City in 2001. Today, Shake Shack operates some 360 restaurants worldwide in 83 countries, generating about $740 million in annual revenues.

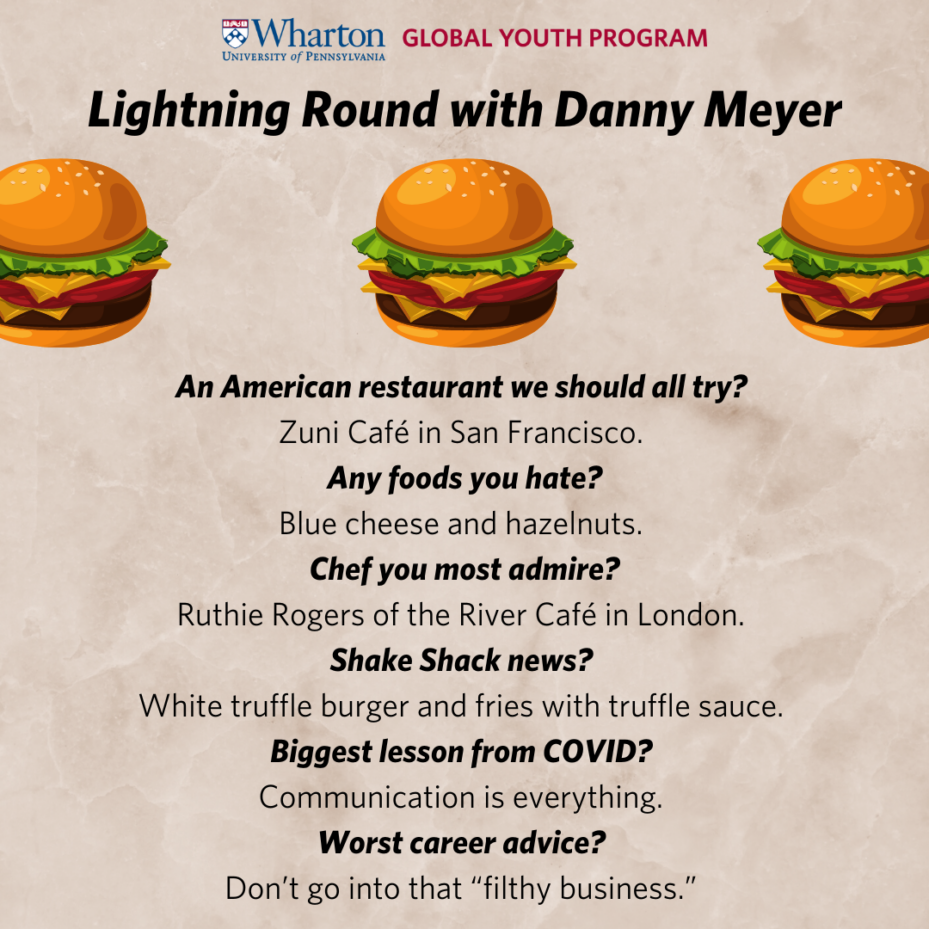

In a career spanning 40 years, Meyer has collected stories and business insights, many of which he shared in his book Setting the Table, published in 2006. He recently visited the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania for a McNulty Leadership Program Authors@Wharton interview with Adam Grant, a Wharton professor and thought leader in management and workplace dynamics.

Here are 4 tasty tidbits from their conversation:

The LSATs, an uncle, and a course correction. You’ve heard it before – follow your passion. That’s not always so easy to identify. Such was the case for Meyer who, after taking a first job out of college selling electronic tags to stop shoplifters (he was a star salesman!), decided to become a lawyer. The night before his Law School Admission Test, he joined his aunt, uncle and grandmother for dinner at an Italian restaurant in New York City. He was anxious about the test, mostly because he wasn’t excited about becoming a lawyer. “That night my uncle asked me the best question I have every been asked,” recalled Meyer. “He said, ‘Do you have any idea how long you’re going to be dead?’ I said no, I hadn’t really thought about it. He said, ‘I don’t know either, but it is a hell of a lot longer than you’re going to be alive. Why in the world would you do something you have no passion around?’ I said, I don’t know what else I could do. He said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me. All I’ve ever heard you talk about your whole life is restaurants and food.’ From there, Meyer took a restaurant-management course (after gathering the courage to tell his parents his new plan), got an entry-level job at a restaurant, and never looked back.

Salmon and stakeholders. A recurring theme around Meyer’s business decisions has been getting mad as a motivator. After becoming successful with Union Square Café, he decided to start a second restaurant, Gramercy Tavern. A long-time satisfied Union Square customer came up to him one day after eating lunch at Gramercy and said, ‘You’re never going to make it here.’ The restaurant staff had not acknowledged her plate of uneaten (overcooked) salmon for the entire meal, and then wrapped it up for her to take home – something that never would have happened at Union Square. Meyer stewed over this poor service for a few days, called an all-staff meeting, and presented what would evolve into his signature business model for long-term, sustained profitability: enlightened hospitality. “I said, we have the exact same five stakeholders as every business on earth,” noted Meyer, naming them as employees, guests, community, suppliers and investors. “We get to pick the order in which we are going to prioritize them,” starting with ourselves (employees) and ending with investors. “The thing I expect is to create a virtuous cycle, where one good thing leads to something even better. If you want to have really happy investors, then you better make sure all those other inputs are singing…The cool thing is that this has been the operating system for every single thing I’ve ever done.”

“The biggest misperception people think about me is that Mr. Hospitality is not incredibly competitive.” -Danny Meyer

Taking risks, topped with mustard and pickle relish. Given Meyer’s strong reputation in fine dining, most people didn’t expect him to experiment with another segment of the restaurant industry, like fast food. But he got tired (mad!) of people saying that his enlightened hospitality approach only applied to upscale restaurants. When he was approached to consider opening a hot dog cart as part of an art installation in Madison Square Park, he jumped at the chance, choosing to make Chicago-style hotdogs with a choice of eight classic toppings. “My colleagues looked at me like I was crazy,” he recalled. “I wanted to see if we could infuse a hot dog cart with hospitality…and we had lines around the corner. I came up with [the name] Shake Shack. I had no idea it would turn into a business, a public company [or] an international company.” What’s the most important question to ask yourself when you’re considering taking a big risk? “How will I handle things when they go right? I think that’s part of the curse and blessing of being an entrepreneur. It’s important to ask yourself, what if this works?”

French fries prove the power of intuition and evidence. While researchers like Adam Grant approach problems by analyzing data and information, Meyer admits to being a more intuitive decision-maker who relies on instincts and experiences. He has, however, learned the value of both intuition and evidence. Following a poor New York Times review of Shake Shack in which the writer called out the restaurant for serving frozen, not fresh fries, Meyer took action. “It really got under my craw, and I said, we’re going to show him,” said Meyer (mad again!). He converted all existing Shake Shacks (at the time around 30) to begin serving fresh French fries. Little did he know – because he hadn’t done the research – that you’ve got to fry fresh potatoes three separate times and hang them between each oil dip. Even then, for a variety of reasons, the quality and taste are inconsistent. “Frozen fries are picked at peak when fresh and flash frozen so they never change their molecular structure. They’re actually coated with something that acts like a raincoat, sealing in the heat, sealing out the oil,” Meyer explained. “We were so proud and free of evidence and not listening, and it was the biggest lesson that I think we learned,” said Meyer, who after more than a year decided to bring back Shake Shack’s frozen crinkle cut fries, improved with non-GMO potatoes. “That was the biggest one-day bump in business we’ve ever had.”

In the competitive restaurant business, Meyer has long focused on quality goods and services, variety and innovation. And he wants you to know his least favorite expression: nice guys finish last. “The biggest misperception people think about me is that Mr. Hospitality is not incredibly competitive,” he said. “I love winning, and I think that hospitality is a perfectly fine competitive trait.” In fact, suggested Grant, it may well be Danny Meyer’s competitive edge.

Conversation Starters

Are you a Shake Shack regular? Were you surprised to learn about its inception at the hands of an upscale restaurateur?

Wharton’s Adam Grant and Danny Meyer talk about the combination of evidence and intuition. How do you believe the two should strike a balance? Should one be weighted more than another? What is your optimal experience-to-evidence ratio? Have you tested this theory? How?

Why do you think that Danny Meyer says it’s important for entrepreneurs with big ideas to ask themselves what will happen if it works?

I was 3 years old when Shake Shack opened in my neighborhood on the Upper West Side. I promised I’d behave if they bought me a hot dog and crinkle cut fries. We waited in the Shake Shack line for what seemed like decades before we finally reached the front. Bursting with enthusiasm, I also picked a chocolate shake. Some of my first memories are of the excitement I felt while waiting on line at one of the first Shake Shack locations. Almost nothing made my younger self as excited as a hotdog the size of my torso. This seems to be Danny Meyer’s vision for starting Shake Shack, an affordable, delicious alternative to his background in fine dining.

Danny Meyer’s conversion from lawyer to chef is inspiring in many forms. He discusses how he was taking a traditional path, before his uncle changed his mind. Meyer always had a culinary passion, which is clear through his product. This theme of success through passion is evident throughout the article. Meyer talks about how his love for his work is what led to his success in the culinary industry “In the competitive restaurant business, Meyer has long focused on quality goods and services, variety and innovation.” This quote continues the narrative of dedication and determination that has led to Meyer’s success.

Throughout the history of entrepreneurship, commitment and zeal is a recipe for success. This stays true with Danny Meyer and his fierce devotion to his business. I have continued to frequent Shake Shack over the years, and I’ve noticed that they are constantly crafting new ideas, ensuring Shake Shack evolves. This consistent and lasting drive sets Shake Shack apart from its competitors, making it prosper to this day.

An attribute of entrepreneurship that I particularly enjoy is the power to invest in what you yourself are interested in – for you yourself to be the individual to expand your own ideas. A significant idea explored in this article is how Mr. Meyer took the initiative to operate his successful food business, Shake Shack, along with his personal experience regarding the expression of passion and his thorny path toward it.

Originally, Mr. Meyer had wanted to become a lawyer, but this thought was countered by his uncle’s comment at a dinner: “Do you have any idea how long you’re going to be dead… I don’t know either, but it is a hell of a lot longer than you’re going to be alive. Why in the world would you do something you have no passion around?” What made this quote stick with me was how it traces back to my personal experience with passion and interest. Knowing what you want and doing it – this is a quality that I admired and yearned for and was a feature that I initially thought every business person was born with. However, entrepreneur Mr. Meyer himself proves a stark contrast to this notion.

After prep class, in the car, hands resting on my legs and eyes flickering with the lights on the street. My mom is interrogating me with one hand, and driving with the other, eyes occasionally on the rearview mirror, gazing at me with a piercing curiosity. This situation is not a rare occurrence. I stare out the open window, all I could hear were the whispering winds outside.

“Ni you jiang lai de ji hua, dui ma?”

You have plans for the future, right?

She begins driving faster. The tracking on the car screen read: 27. 29. 31. 35. I could feel the power of the vehicle as it pushed me back into my seat with a whirl. The wind hit my face, propelling me back into reality.

“Ni jiang lai ying gai dang yi sheng, kai xi.”

You should become a doctor, Kathy.

She makes a turn to the right, my body being swayed to the left. I sigh, opening the window even more.

“Wo bu zhi dao.”

I don’t know, I said.

We pull up into the drive-thru of the fast-food restaurant, the gravel on the ground scratching the car tires. I look out of the now gaping window and examine the menu, with an intense desire for something that will quench my thirst. Something sweet, perhaps.

“Can I have a lemonade, mama?”

“No. It is not healthy. I will get a water for you instead.”

… Do I really want a lemonade? No, it’s not that healthy. And it would be a waste of money. Why would I go for a lemonade when they offer free water? My mom might be right, water provides more benefits and tastes fresher.

…

But I can’t. I really like lemonade. Water or lemonade? Water or lemonade? Doctor or teacher?

For me, these two questions seemed to parallel each other. Similarly to Mr. Meyer, I wasn’t sure of what I wanted, although the choice may have seemed obvious. One of the options was healthier, cheaper, and widely approved. The second option was unhealthy, more expensive, and may or may not be the literal cause of diabetes. But, to be frank, I knew what I wanted.

“…I’ll have a lemonade, please.”

I caved. My hunger saw only the lemonade. It was the only item I was interested in on that menu, and I knew I would regret it if I bought water. However, that small experience would later push me through decisions I would make in the future. It created a mental reminder for me that what others said did not dictate what I could truly achieve, for it was only me and the initiatives I took that determine my future. If I didn’t want water, I would not get it. If I was interested in a lemonade, I would get it.

Previously, I had been completely convinced that I was on a path toward the field of medicine, even going as far as to look into the different types: pediatrician, nurse, dentist. Sparkling water, distilled water, tap water – I never refused any type of it. I took it as they came from my parents, and did not complain. But now, I felt something different – I felt a growing discomfort as I skimmed through the dozens of “Medical Field Career” sites. A growing hesitation. It was time for something new. It was only when I found something to ignite my passion that I became fully immersed in and conscious of what I truly wanted. I spent the weeks before summer scrolling through websites and searching through documents for an opportunity to begin my path of change. I found little to no programs for students my age, until I stumbled onto a student-initiated site, reading:

VIRTUAL TUTORING PROGRAM! TUTORS NEEDED: KIDS GRADES 7-12.

Yes. This…this will work. This is the opportunity I needed. This is what I was looking for. This is the initiative I need to take.

Ice, cold, lemonade.

Through this Comment contest program, I was able to delve deep into an article that I was interested in. Among the wide variety of available compositions, this one, in particular, assisted me in exploring entrepreneurship. Like Mr. Meyer with his journey to restaurant work, I was not sure what I was to expect from reading these articles. However, little did I know that I would find inspiration for both new writing and new ideas here. Not everything comes directly to you, and you may find your desires in the least expected places – even in a Shake Shack drive-thru.

Believing in yourself is a powerful and transformative mindset that can propel you to great heights. When you have faith in your abilities, talents, and potential, you can unlock a limitless well of courage, determination, and resilience. Belief in oneself enables you to conquer doubts, embrace challenges, and persevere in the face of adversity.

I love your comment! Using a story of choosing between lemonade and water to illustrate your future choice in your career is great. I really enjoyed reading it! I had a similar experience in terms of believing in myself and not letting anybody get in my way.

My sophomore year, I had the opportunity to play on my school’s varsity squash team. After a poor regular season, we barely made our way to the New England Interscholastic Squash Association Tournament. Our record was pretty bad during the regular season. Out of the 10 teams in the tournament, we were ranked 8th. After telling that to my best friend, he joked about it by saying we should just forfeit due to how bad we were.

Nevertheless, the tournament was a week later, and we were well prepared. Being the underdogs, my teammates and I were really relaxed; instead worrying about wins and losses, we played loose. I started to take more kill shots and tricky shots, something I had never dared to do in regular season play. Because of our positive mindset, we ended up beating a lot of opponents better than us, and we made it to the final.

Before the final match began, I texted the same friend who’d doubted me. He replied: “Damn! Congrats!” In the final, however, our great form came to an end, and we lost 4-2 to the strongest team we’d faced. Despite the defeat, making it to the final was itself a great accomplishment, and our team was proud of that. I’ll be back on the team this school year, more excited than ever to play squash.

After this precious experience, I learned that we should always trust and believe in ourselves, and not let anybody else impact our mindset. This underlying principle can apply in business, sports, relationships, or almost anywhere. My experience played out just like you described in your own decision to choose the career you wanted rather than the career you were expected to pursue. “It created a mental reminder for me that what others said did not dictate what I could truly achieve, for it was only me and the initiatives I took that determined my future.” The critics did not dictate what me or my team could achieve, because I, myself, am the one who is in charge of my future.

Embedded within entrepreneurship, is the characteristic of decision-making, a trait that has long alluded to understanding. I have always respected the way that everyone’s approach to decisions are different and find it interesting the way that Danny Meyer, throughout his career made the ones he did. Meyers created a fast food empire through a line of risky decisions that most people wouldn’t dare take, unlike him who did it without looking back. Danny stayed true to his ideals of prioritization and hospitality while managing to implement it into an industry where those traits have alluded competitors. I still remember visiting Shake Shake for the first time, I was 10, hangry inside the airport, basically forcing my dad to buy me some food. I ended up pulling him right in front of the Shake Shack completely by accident (I was trying to go to McDonalds to get chicken nuggets like any other 10 year old would) and saw it completely full. I was instantly captivated by the huge photo of my now favorite milkshake, the Black & White Shake. My dad noticed my sudden change in demeanor, my walk screeching to a halt, my face in awe, and simply said “If I get you a milkshake and burger I better not hear a word about needing to go to the bathroom in the car home.” to which I simply nodded. I remember walking up to the counter and being so short my dad held me up to be face to face with the cashier. They were extremely nice and attentive to me, helping me pick out options and On that fateful day, I, too, made a seemingly “risky” decision, mirroring the choices Meyer was compelled to make throughout his journey. However, amidst the uncertainties, he remained steadfast in his commitment to the values of hospitality and prioritization. The courteous attendant exemplified a dedication to prioritizing customers’ needs, extending an exemplary level of hospitality that forever transformed my perception of fast food. Danny Meyer’s unwavering dedication to his ideals shines through every decision he makes, much like my unwavering commitment to ordering my beloved Avocado Bacon Burger paired with a Black and White Shake whenever I find myself at the airport.

I was introduced to shake shack a lot later in my life than most people. However, I distinctly remember the food being unforgettable.

Danny Meyer is truly an inspiration. He was able to pursue his dreams regardless of what his parents said and not having any guidelines. He refused to give up and is a very successful owning multiple restaurants. He serves as a powerful example to us all that we can be successful by pursuing our dreams.

I believe that its important for entrepreneurs to think about the what’s next step. Although I am not an entrepreneur, I find myself always caught up in the present failing to think about how the outcome will affect me in the future. If I took those few minutes to just reason, I feel like I would be a lot more organized in thought as well as determined to myself that future.

“Do you have any idea how long you’re going to be dead?” This question asked by Meyer’s uncle prompted him to shift his career towards his love for restaurants and food, a decision I found incredibly inspiring.

In some ways, Meyer’s decision to follow his passions resonates with my own experiences. In my case, this situation was reflected through choosing between what others expected of me and what I truly love. Coming from a Chinese household, my parents often encouraged me to pursue the stereotypical STEM and math route, but my real passion has always been in business and entrepreneurship.

Growing up, I always watched episodes of Shark Tank, dreaming of becoming a successful business owner like Mark Cuban or Kevin O’Leary. However, as a middle school student, I was afraid to pursue that dream because in our culture filial piety meant I always listened to my parents. I wish I had encountered Meyer’s story earlier in my life; it might have given me the courage to pursue my interests in business and economics without hesitation.

Meyer’s bravery to pursue his passion is not the only thing I admire though. The article’s exploration of Meyer’s concept of “enlightened hospitality” challenged my preconceived notions about business priorities. Meyer’s approach emphasizes a hierarchy that begins with employees and ends with investors, fostering a “virtuous cycle” where satisfied employees lead to happy customers, which in turn benefits the community and investors. This method contrasts with traditional business models that I have been introduced to, one that often prioritize investor satisfaction above all else. As Meyer expressed, “If you want to have really happy investors, then you better make sure all those other inputs are singing.” This philosophy underlines the importance of considering human motivations and relationships in business models.

Another part of the article that I found interesting was the discussion on intuition versus evidence in decision-making. Meyer’s decision to switch Shake Shack’s fries from frozen to fresh based on intuition, only to switch back after realizing the benefits of frozen fries, showed the importance of balancing instinct with verifiable data. His experience made me understand that while intuition can guide innovation, evidence-based adjustments are crucial for sustaining success. Meyer admitted, “We were so proud and free of evidence and not listening, and it was the biggest lesson that I think we learned.” His experience highlighted the need for flexibility and learning from mistakes.

From valuable insights into entrepreneurial strategies to the intersection of intuition, evidence, and human behavior in business, I personally feel like I gained a lot from reading this article. As I prepare for my course at Wharton LBW this summer, I am excited to dive deeper into these concepts, learning from both theories and real-world examples like Danny Meyer’s and ultimately applying these lessons to my own entrepreneurial pursuits.

My most ambitious project yet has been my fish tank. It was my first time actually caring for an animal. After meticulous research, I decided the best starter fish would be rosy barbs, a shoaling species that is meant to be kept in groups of at least four or five. Due to eagerness, I went ahead and started the fish tank immediately after understanding the basics. I figured that the rosy barbs wouldn’t last very long, so my first attempt at fishkeeping would be trial and error so that the second attempt would be better. With this in mind, I spent less time researching information thoroughly and bought everything as soon as I could. What I didn’t realize was that the fish were hardier than I expected. After the first fish died due to getting an illness from being bullied by the others, I became paranoid about the other fish dying. It stressed me out for days. What if the bullying got worse? What if there’s chlorine? Ammonia? I bought several medications and some aquarium salt just in case.

I agree with Mr. Danny Meyer that an important question to ask is “What if this works?” Because I didn’t do so, I neglected a lot of information that could have streamlined the beginning, such as washing excess carbon dust from filter cartridges and kickstarting the nitrogen cycle before adding in fish. It’s easy to say, “Hope for the best, prepare for the worst,” but that only works in short-term scenarios, like if you get a good test grade. In long-term commitments, the mantra may under-prepare us for the maintenance of it. We’re so used to preparing for the worst that we don’t consider the best, which ends up worsening things.

Mr. Meyer’s question also applies to his intuition-evidence dilemma. Sometimes, when the risk is unknown or high, we try to decrease the risk. Similar to Mr. Meyer’s fries situation, I once relied more on my intuition than facts. When presented with evidence and facts that seem strange or unintuitive, it might be easy to dismiss it, but they’re undisputed for a reason. We should trust the facts. Oftentimes, fish are compared to plants: they’re both beginner “pets.” My mom grew plants, in which less is usually better when starting out, so we applied the same logic to fish. My mom told me that, if I could take care of two fish first, only then I could take care of five. We considered five fish too much of a risk for a beginner like me. While that may be true in the case of some species, it is actually worse for shoaling and schooling ones, such as rosy barbs. When we bought two fish, the larger one bullied the smaller one so badly that the very next day I ran to PetCo to buy three more.

Due to this fiasco, I have started to consider the importance of preparing for both the worst and the best. I’d also like to add on to Mr. Meyer’s question and ask, “What would happen if I don’t do this?” I didn’t believe the evidence would work because it’s hard to understand that, on occasion, more is better, especially when it comes to shoaling or schooling fish. In Mr. Meyer’s case, fresh wasn’t better. In my case, less wasn’t better. What is considered common sense or a general rule isn’t applicable to every situation. You might have considered my intuition a bit fishy, but it was an important learning experience. If Mr. Meyer hadn’t experimented, neither he nor the customers would have learned about the benefits of frozen fries. As important as it is to ensure safety, it is equally as important to play around with possibilities. It’s also a question about the opportunity cost. If Mr. Meyer didn’t open Shake Shack, he would have missed out on a giant opportunity. If I didn’t buy a fish tank, my life would not be as interesting as it is now. Sometimes, optimism doesn’t hurt so much.

It astonishes me how the founder of Shake Shack, Danny Meyer, almost became a lawyer instead of following his true passion towards restaurant management. If it weren’t for his uncle’s words that pushed him to pursue his dreams, we wouldn’t be able to enjoy Shake Shack burgers with crinkle-cut fries and a chocolate shake today.

His uncle’s words have also inspired me to contemplate what I actually want to do with my life. There are so many possibilities––so many different paths I can walk down that will all lead me to different places. Kind of like those signs you see on the street that have an arrow pointing in every direction. Which way do I go? If I choose one path, it means I will lose all other possibilities. All my other dreams will slowly slip out of my grasp and evaporate into thin air. Those goals remain unticked, those vision boards covered with dust; those childhood dreams stay dreams, and all those paths start to vanish until I feel completely lost. Which way do I go?

What do you want to be when you grow up?

We’ve been asked that question too many times. Most of us change our answers over time, and at my age many of my peers will still answer with “I don’t know yet” and I think that’s totally fine. We still have plenty of time to make up our mind about things and pursue what we truly desire. But is it normal to stick to a dream that sometimes doesn’t even feel like yours? I ask myself that all the time.

What do you want to be when you grow up?

I watch as my classmates tick all kinds of career fields on their form: from engineering to agriculture; from fashion to psychology––to me it seems like they have an interest in everything.

My pen hovers over the field reading: FINANCE/BUSINESS/ECONOMICS. Is this what I really want? It’s not that I don’t have any interest in it, but sometimes I wish I went down a different path, but which?

Medicine?

No.

Law?

No.

I hesitate but my pen already ticks the box. I make my way to the front and hand my form to the teacher before I regret it. What else is there?

Maybe I just need a dinner with my uncle.

“Hey, do you know what you are going to do in the future?”

“Any ideas for college majors yet?”

“What do you want to be?”

Questions like this are being thrown at students all the time – in school, at dinnertables, over boba with friends, and repeatedly in our own mind. Many of my other high school peers and I either have a place holder (doctor, lawyer, teacher), no answer at all, or too many options. From first grade to last year, my answer has always been one that made other people nod approvingly – for example, a lawyer from Mr. Meyer’s story.

Recently, I have been frequently thinking about what I want to do in the future. However, the question has shifted from focusing on what would make other people happy to what makes ME happy? What am I passionate about? What do I catch myself doing most in my free time? The answer is art and crafts: sketching, painting, crocheting, DIY projects, etc. Although I had always been under the impression art doesn’t make money, I still decided to explore its potential through finding potential careers online. Animator? Engineer? Architect? Architecture—something that combines STEM, my forte in school, and art, something I am passionate about.

“Ooooo,” I quickly jotted it down in the Notes app.

Now I am taking an online course in engineering, sketching online blueprints for fun, and using YouTube and other platforms to find out more about the major.

As I reflect on what Mr. Meyer’s uncle said about “‘Why in the world would you do something you have no passion around?'”, I can only conclude that he’s absolutely correct. While many may argue that it is an idyllic statement, I think that one who is passionate about something will pour all of their resources into it and as a result will become successful. I believe one should always prioritize themself when thinking about their future. I encourage others that may not have someone like Mr. Meyer’s uncle: observe their actions, pay attention to their interests, and be curious and flexible! While it is unlikely that every teen will know exactly what they want to do for the rest of their life, I have found these steps helpful in one’s own journey.

This past summer, while my sister and I often found quiet comfort sipping Shake Shack’s heavenly cookies and cream shakes after long days, back at our family’s Indian restaurant, the chaos of Teej was unfolding like a storm.

Teej is Ghewar season—the festival where this delicate, honeycomb-textured sweet takes center stage. Ghewar is a labor of tradition and patience. You can’t whip it up on a whim. It requires days of preparation, frying in thin layers, and soaking in syrup that must be just right.

We prepped what we thought would be enough, but almost immediately, the demand overwhelmed us. Our weekly inventory meetings became a kind of suspense thriller. Sitting around the table, staring at the dwindling numbers for ghewar ingredients—flour fine and powdery like dust, ghee with its warm, buttery scent, saffron strands glowing like tiny embers—felt unsettling. Each week, those figures slipped away faster than expected, and it was like watching sand slip through fingers.

When the shipments finally arrived, the aroma of fresh ghee filled the back room, promising relief. But the window to stretch those precious supplies was narrow. Barely unpacked, the ingredients began to disappear again, as if pulled by an invisible tide of hungry hands. Our kitchen buzzed with tension: sizzling oil, the rhythmic clatter of frying pans, and the sweet, sticky scent of syrup filling up the kitchen. Every batch demanded precision and care. Too much syrup, and the ghewar would become soggy; too little, and it would be dry and brittle.

Phones rang nonstop, voices filled with anticipation and hope. Customers called from across town, eager to reserve their share of the festival’s signature treat, some ordering enough to fill tables for family gatherings. My manager and I moved through the frenzy—coordinating orders, managing frantic staff, and soothing anxious customers. The air was thick with a mix of exhaustion, excitement, and the faint sweetness of cardamom and rosewater lingering on everyone’s breath.

This all brought to mind something Danny Meyer emphasized, the idea of prioritizing stakeholders to create a virtuous cycle. Each ingredient represented a promise from suppliers thousands of miles away, each customer’s satisfied smile was a return on that promise, and every kitchen hand sweating over the hot stove was the backbone holding it all together.

There were risks, like running out of ingredients, disappointing loyal customers, but Meyer’s “enlightened hospitality” showed me that the true challenge wasn’t avoiding those risks, but how you respond when they arrive. We had to protect the quality and tradition of our sweets, even as the pressure mounted.

Like Meyer’s story about Shake Shack’s fries, where intuition met evidence, we learned when to hold firm and when to adapt. We couldn’t just make ghewar faster or in larger quantities without risking its delicate texture. The patience and care baked into each batch were what made it special.

Later, as my sister and I savored our cookies and cream shakes in the calm of an evening after the festival rush, I realized something important. Whether it’s managing inventory for Ghewar or running a fast-food empire, business comes down to the delicate balance between respect for tradition, care for people, and the hard work behind the scenes that most don’t see. It’s in those moments, the sizzling kitchen, the ringing phones, the tired smiles, that the real story of business is written.