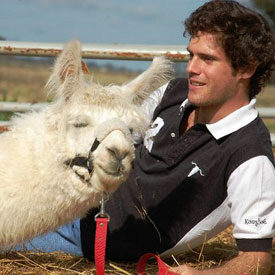

Gustavo Maluéndez was 11 years old when he convinced his father to buy some small llamas from northern Argentina and take care of them as pets. He never imagined that his hobby would become an international enterprise selling animals and producing high-quality garments.

Maluéndez, now a 25-year-old student of political science, became famous in his country when the government of Oman, headed by Sultan Qaboos bin Said, signed a contract with him to provide 12 llamas that could do tricks during festivities for the 40th anniversary of the Sultanate in November 2010. It all began when an intermediary from the Sultanate visited Maluéndez’s web page at www.camelidos.com, and wrote him about possibly buying llamas for “a celebration.” At first, Maluéndez thought it was a joke, but a royal retinue from Oman went to Argentina to get to know him and make sure that they were dealing with creatures of high quality.

Maluéndez spoke to Knowledge@Wharton High School about the roots of his business and where he hopes his love for llamas will lead.

Knowledge@Wharton High School: What was it like when you were getting started with your business?

Gustavo Maluéndez: It all happened by accident. My family has a small farm where they raise cattle in the city of La Plata, and they went there every weekend when I was a kid. Along with my brothers, we vaccinated the animals, who were mostly females, and we “played” at being cattlemen. Every year, we also visited Argentina’s Rural Exposition (the oldest agricultural expo in Latin America), where my attention was drawn to a particular sort of llama in the show. I convinced my dad to buy me [some] and we began by raising two males and two females. I was still studying in high school.

KWHS: Why did you decide to focus on llamas?

Maluéndez: They seemed gorgeous to me. My dad saw my passion for llamas and he helped me set up the breeding place. Without realizing it, I did things that had to do with company management, such as filling out paperwork with information about each animal. When I was in the fourth year of high school, I showed one animal to a school friend — who was very good at drawing – and he created a logo for the company, for which I paid him 5 pesos (US$1.25).

KWHS: When did your hobby actually turn into a business?

Maluéndez: It was in 2002, when I was in the last year of high school, and I was already prepared to participate in the Rural Exposition with a female llama. That year, three ranches were competing, and our business was just getting started. Of the 18 animals [in the competition], my llama emerged as grand champion. Our neighbors in the countryside began to learn about our work, and they became the first to buy our llamas.

KWHS: How did you expand the business?

Maluéndez: People were finding out that we were raising llamas – something quite uncommon in Buenos Aires – and they began to buy animals to keep as pets. The average cost of an animal is 1,800 pesos (US$450). In addition, we were continuing to win prizes so we decided to make an important purchase of 100 animals in the north, which cost us about 30,000 pesos (US$7,500). My dad considered it a loan for me, with the idea that I would manage everything all by myself.

In 2006, I created a corporation called Gulla – “Gu” for my first name Gustavo and “lla” for the word llama — because someone in Uruguay had contacted me about buying about 300 llamas. According to sheep producers in that country, llamas were the ideal animals for taking care of their herds. There were no previous examples in Argentina of any llama exports, so it took us almost a year to put together three shipments.

KWHS: How did you wind up in the textile business?

Maluéndez: To keep the animals from dying, I needed to start shearing them and look for a place to sell their wool. I decided to send the wool to a group of craftsmen in the province of Jujuy in the north of Argentina, where these animals came from. I began to buy other types of these animals [for the craftsmen] and helped them with microloans [small amounts of money loaned to people in developing countries to help them get started in business]: I advanced them money on a weekly basis, and they repaid me by working for me. That way, they acquired more working skills; in fact, last year they launched a workshop and a storehouse for gathering fibers. Now each craftsman has his own loom and his own bank account.

KWHS: What are your strengths in operating this business?

Maluéndez: It has been very important to keep my eyes open and be aware of every opportunity. For example, in the case of exporting llamas to Oman, it all began with one e-mail. Anyone might have been surprised to face the challenge of training 12 llamas over four months for a sultan; this was something that had never been done before. This kind of situation only occurs once in a lifetime.

KWHS: What have been your biggest problems?

Maluéndez: One of my biggest problems has been to develop the marketing [campaign] for an unknown product, especially in a foreign country. Beyond that, I am also competing against the Peruvian alpaca, whose producers have a lot more experience at exporting and marketing. In addition, their product is more industrialized. I’ve tried to differentiate myself from the alpaca through high-quality workmanship.

KWHS: Where do you see yourself five years from now?

Maluéndez: I [would like to] devote myself seriously to the production of fiber. I believe this will generate the most long-term return, since the average garment sells for some 600 pesos (US$150). Over the next five to 10 years, I’m betting on becoming a leading provider of finished high-quality products — such as sweaters, ponchos and ruanas — in the major cities of the United States and Europe.

Related Links

Conversation Starters

What does Gustavo Maluéndez’s business say about turning a passion into a promising enterprise? Beyond a love of animals, what business sense did Gustavo need to take his idea to the next step?

Is Gulla still in business? Research it online and find out whether Gustavo made his dream a reality.