A High School Educator’s Experience Co-teaching a Remote College Course

In July 2021 Katharine Chambers, a finance teacher at Manchester High School in Connecticut, received a curious email from her principal. Would she like to help teach a special personal finance class to a select number of Manchester students that had been designed and would be taught remotely by the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania?

“I really thought about it because I didn’t want to take on anything I couldn’t manage,” says Chambers, a long-time educator who already had five full classes to teach when school started that September. “I responded within a week and said, ‘This really speaks to me.’ I liked the opportunity for the kids and I liked the college environment.”

Chambers was one of eight teachers from eight schools around the country to take part in a pilot partnership between high schools and higher education.

In the fall of 2021, the Wharton School, in collaboration with the National Education Equity Lab, began offering the course Essentials of Personal Finance, which was designed to teach personal finance concepts and financial decision-making to disadvantaged high school students. Across 10 weeks, students would learn everything from defining and calculating simple and compound interest, to how the U.S. tax system works, to exploring ways to fund higher education and negotiate the best available financial aid packages. The course, developed by Wharton’s Stevens Center for Innovation in Finance, was an extension of the Wharton Global Youth Program’s credit-bearing Pre-Baccalaureate Program to underserved communities in the U.S.

“My students really connected with their teaching fellows and got to see another lifestyle, which is huge for our school as one of the most diverse in Connecticut.”

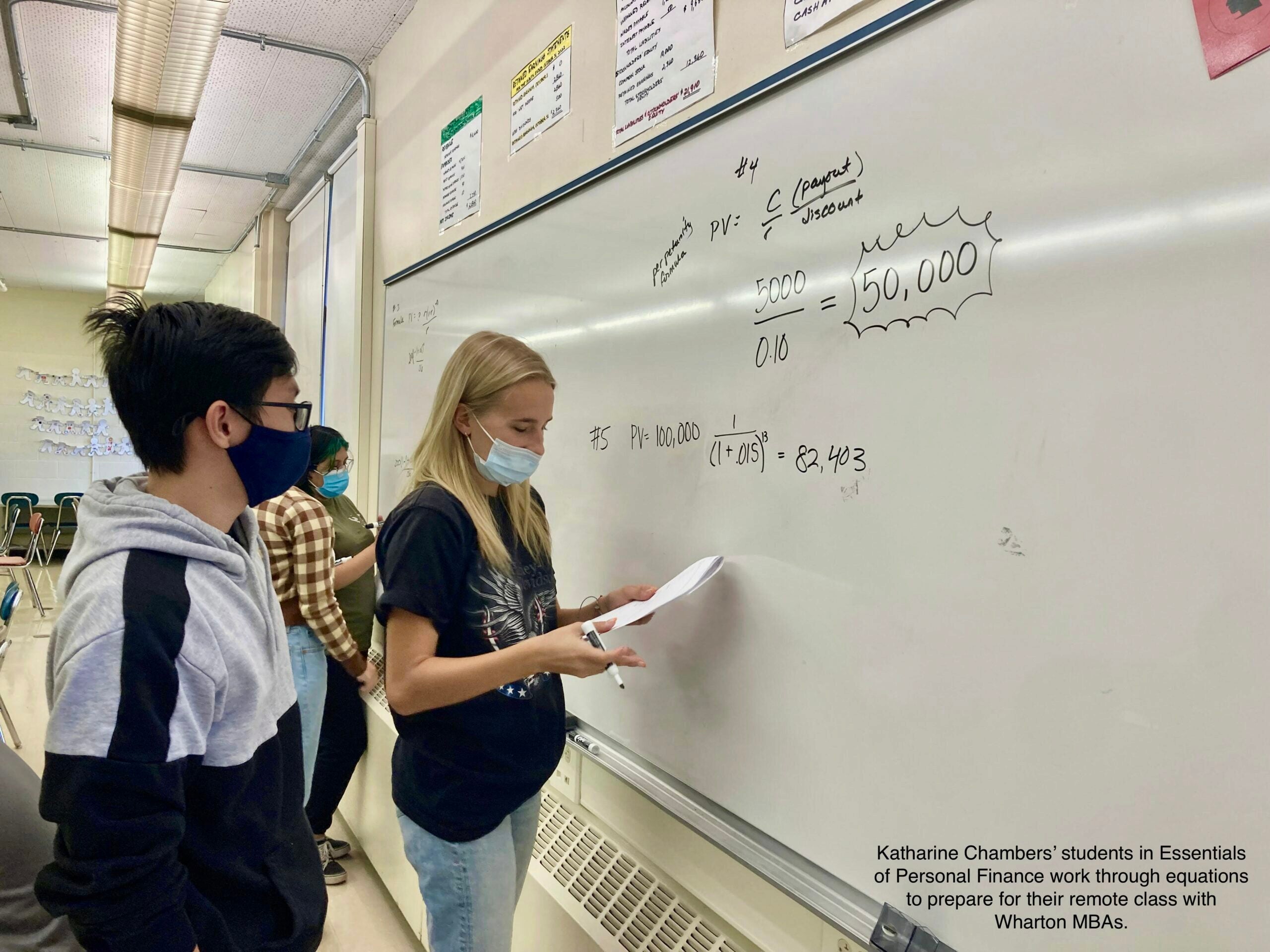

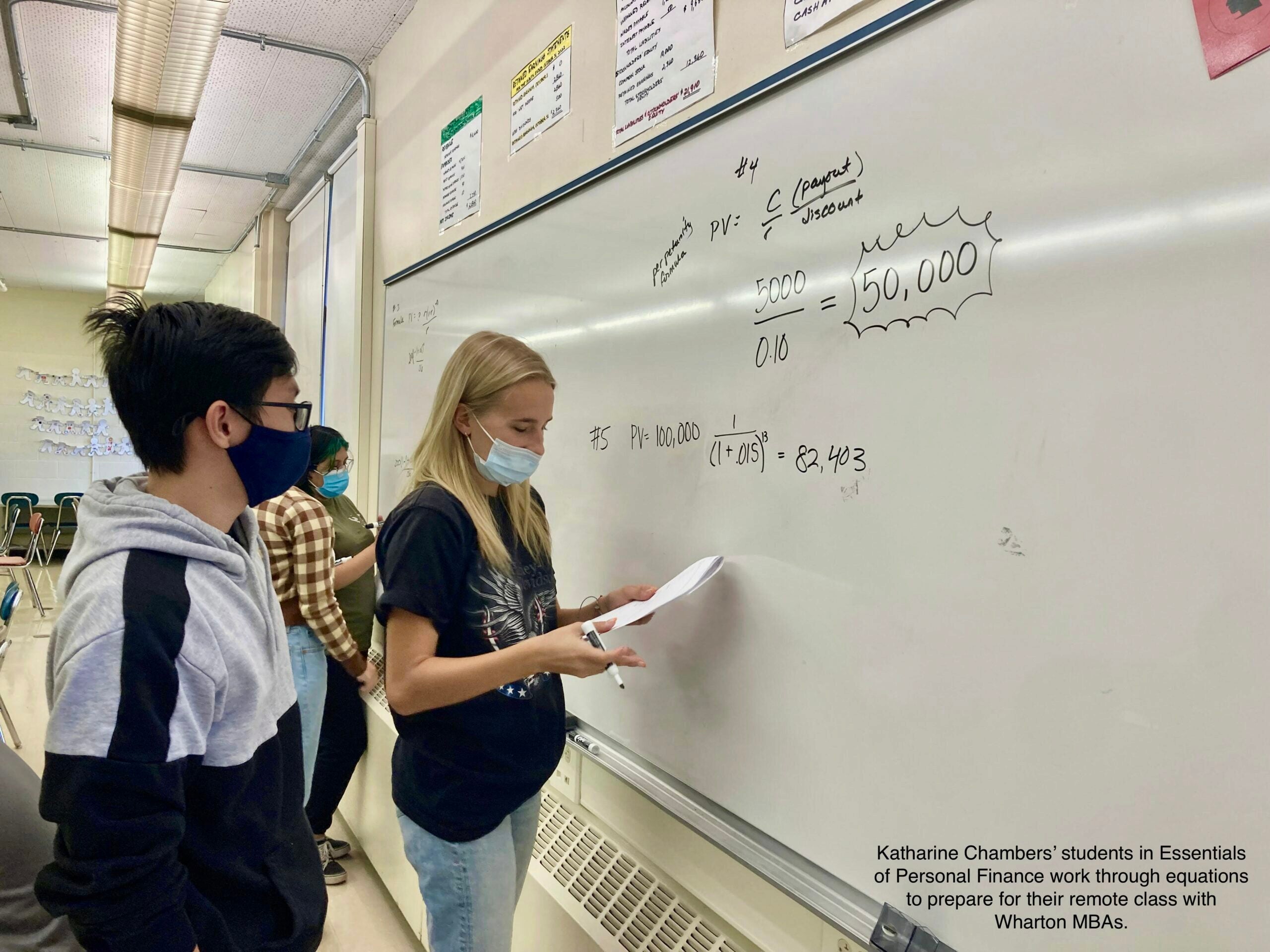

As a co-teacher in this different education-delivery model, Chambers was responsible for guiding the 10 Manchester juniors and seniors in her class, while two MBA students from Wharton – known as teaching fellows – connected with those students weekly for 45 minutes over Zoom to teach the course material. Chambers was face-to-face with the kids and the fellows were online, creating a unique teaching collaboration.

“We made the virtual format work,” notes Chambers. “I set up my Google Classroom and posted their reading assignments from Wharton. We met three or four times a week in school and then they met with the teaching fellows, Jasmine and Alex, every Tuesday at 6 p.m. There’s a lot teachers can do with this type of partnership. We do have a role to play.”

Chambers emerged from the 10-week course with great insights about the co-teaching experience that she wants to share with other educators:

Get comfortable being uncomfortable. The course took learning to a new level, says Chambers, who wrote her high school’s personal finance curriculum and has taught it for many years. “The classes started off with the present value of annuity. My students didn’t know present value or annuity,” she recalls. “But that was okay. I liked the fact that it started off with a bang and really set the tone that this is a serious college class. I held the standard. Our expression was: we’re all going to dig in!”

Matching with another curriculum. Chambers’ job was to bring the Wharton material down to her students’ level. “I provided the scaffold,” she says. “I would meet with them before their Wharton class to give them some background information and prepare them to discuss the topics. I liked the fact that even I was uncomfortable with some of the material and had to really think about how to break it down for them. It was a growth experience to match with another curriculum. I also provided additional information before and after the course from my own materials on topics like budgeting, and I used case studies.”

Being observant and addressing concerns. Even the most dedicated 17-year-olds are going to push the limits, says Chambers, especially if they have jobs, take care of younger siblings and have several AP classes. “When there was talk about students not attending the online classes or not getting their quizzes in on time, I provided the accountability,” she notes. “I made doing the reading a grade. I made recitations [online meetings] a grade. I held them accountable for their actions. This also helped because the kids were on two transcripts, one through Manchester and one through Wharton. They were being graded through both.”

Keeping it current. Even with a wealth of finance resources for the classroom, few will be as timely as a business school on the cutting edge. “Alex and Jasmine went above and beyond with their support,” notes Chambers. “My students had an interest in cryptocurrency, so they brought in a graduate student as a guest speaker to answer our questions.”

The value in higher-ed connections. The Essentials of Personal Finance embedded course inspired students to see another life and to dream different dreams. “My students felt empowered,” says Chambers. “The course has value in not just the content, but the experience of it all. My students really connected with their teaching fellows and got to see another lifestyle, which is huge for our school as one of the most diverse in Connecticut. They asked Jasmine and Alex personal questions, like what do you have in student loans and how do you make this work? The fellows were honest about dealing with some credit card debt. There was a lot of personal give and take in these conversations. It was invaluable for my students to be exposed to this.”

Chambers plans to co-teach another Wharton course in the spring of 2023. What will she be expecting from her students? “I want them to really understand how unique this opportunity is and what it means to them,” she says. “The first time was magical. I’m looking for that magic again.”