How to Discover Potential in Yourself and Others

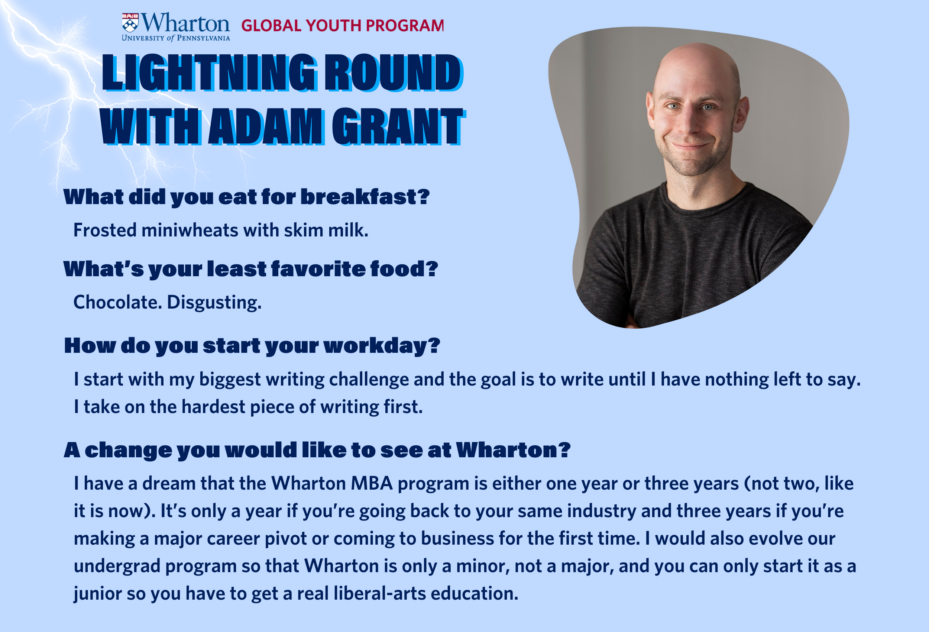

Adam Grant is more than a management and organizational psychology professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He is a powerhouse brand. Dr. Grant has been recognized as Wharton’s top-rated professor for seven straight years and is a No. 1 New York Times bestselling author of six books and a popular podcaster. His inspiring insights circulate around social media at lightning speed. Like this one: “The highest compliment from someone who disagrees with you is not, ‘You were right.’ It’s, ‘You made me think.’”

In the spirit of thoughtful reflection, we are exploring Adam Grant’s latest bestseller, Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things. Dr. Grant sat down with fellow Wharton and Penn professor Angela Duckworth for a conversation about why unlocking potential isn’t always about talent.

In the spirit of thoughtful reflection, we are exploring Adam Grant’s latest bestseller, Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things. Dr. Grant sat down with fellow Wharton and Penn professor Angela Duckworth for a conversation about why unlocking potential isn’t always about talent.

Adam Grant: Sports Star

Their conversation kicked off from a very relatable place for many high school students: sports achievement.

Dr. Grant’s playing field back in his hometown of West Bloomfield, Michigan, was the pool, where as a high school freshman he decided to try diving when he didn’t make the basketball team. “I was hands down the worst diver on the team,” admitted Grant.

How did he progress from belly flops to All-American diver by the time he graduated? “I remember [my coach] saying to me that I got further with less talent than anyone he had ever coached,” noted Grant. “I think it’s a huge compliment. I don’t know if my potential was hidden or if I just squeezed every ounce out of it. The lesson here is that I had real talent constraints, and I had a coach who taught me what grit looked like and to learn that I was able to improve at a faster rate and get to a higher level than ever expected. One season my coach said, ‘Every day at 6:00 practice is over, and I have to kick Adam out of the pool.’ I would always say, ‘Just one more dive’…What kept bringing me back was I loved being part of a team. I loved challenging myself to do something where I could get better, even though I wasn’t very good.”

This personal story, one of many that author Grant pairs with evidence and insight, captures the essence of his book. While we live in a world that is obsessed with talent and over-achievement in the form of gifted athletes, music prodigies and straight A students, we often underestimate the range of skills that we can learn and how good we can become. As he puts it: “Admiring people who start out with innate advantages leads us to overlook the distance we ourselves can travel.”

Learning to Accept Criticism

Professor Grant’s book explores how to build the character skills and motivational forces to realize your own potential. His research often challenges existing practices and presents a new way of thinking about things.

During his conversation with Professor Duckworth, he discussed accepting criticism, which is not the easiest skill for most teenagers (or adults!), and yet is an essential part of personal growth. We all need to learn how to do it better.

Dr. Grant suggested starting with a feedback filter and then following a specific strategy for accepting criticism. “Not all critics are thinking critically about you and not all critics are speaking constructively about you,” he said. “You need a filter to figure out whose criticism is worth listening to. In some cases, you should discount them because they don’t know what they’re talking about task-wise; they don’t have relevant expertise. In other cases, they are very familiar with the task, but they don’t know anything about you and your capabilities so what they’re saying may be miscalibrated. And most importantly, even if they’re an expert on you and the task, if they’re not trying to help you –they’re envious of you or they’re threatened by you — then you have to question whether what they’re saying is really going to be helpful to you.”

If you conclude they are a credible criticism source, Grant embraces a concept from conflict-mediation expert Sheila Keen, known as the second score. “When someone gives you feedback, you usually try to argue with them about the score they gave you. Instead of trying to change the first score, you should try to get an A+ (the second score) for how well you [respond].” In other words, shift your focus to getting a perfect score for how well you accept and process the criticism. Visit this Huberman Lab podcast segment for a personal story about how Dr. Grant has used the second score in his career.

Antique Apples and a Chance to Shine

Strategies for unlocking potential must also involve designing systems that create opportunities for those who have been underrated and overlooked, said Grant. He and Dr. Duckworth discussed several of these systemic improvements, which he hopes will make their way onto campuses and into business boardrooms and corner CEO offices.

The big mistake we make when assessing potential in others, for instance, is that we listen to what people say, instead of watching what they do. “How many times have you admitted someone who is a great talker or hired somebody who is charismatic and incredible at schmoozing, only to find that they didn’t have the skills or motivation that you were looking for? asked Grant.

He illustrated how to get closer to seeing real motivation and skill through his own experience selling advertisements in college for Let’s Go books.

“I had a candidate come in [for a job] and he gave a terrible interview, and I rejected him,” Dr. Grant recalled. “I said, ‘I can’t hire this guy for sales. He didn’t make any eye contact.’ [My supervisor] said, ‘You realize this is a phone sales job, right?’ It hadn’t crossed my mind. I was looking to gauge social skill, and he failed. We called that candidate back for a do-over and asked him to sell us a rotten apple. Without skipping a beat, he said: ‘This may look like a rotten apple, but I’m actually selling aged, antique apples. You can display this on your mantle, and you only have to eat one a week for the benefits, and when you’re done you can plant the seeds in your backyard and you won’t have to buy seeds at the store.’ He was the highest-performing salesperson we ever hired. He was extremely introverted and built robots. Once we gave him a chance to shine, he was able to get creative.”

This concept of the do-over is something that Adam Grant wants potential-seekers (you!) to remember – and future employers (you!) to practice as they look for the hidden potential in others. “We all need a do-over. I think that every organization at every job should do this,” he said. He cited the example of one hiring manager who gives job candidates a second chance if they’re unhappy with how the interview went, and also has them fill out a questionnaire about their strengths, and then gears the interview around what candidates think they do well, rather than playing “gotcha” with his questions. “Your interviewer is your literal host whose job is to help you put your best foot forward,” marveled Grant. “I would love to see that be the norm.”

Help Others Stand Out and Fit In

According to Grant, companies often fail at unlocking hidden potential in their employees, because they try to break people in to fit the mold of the organization, as opposed to letting them stand out. “What does it take to see somebody’s hidden potential and allow them to be distinctive from day one? One of my favorite things to do is a personal-highlight reel,” he said. “In your first week on the job, you’re asked to imagine that you’re going to be on Sports Center tomorrow showing the highlights of your life or your career; the moments that you’re proudest of and that you were at your best. You share those with your manager and the rest of your team. When people are given the chance to do that, they feel like they stand out, but they also fit in because people start to see them as unique human beings and value them.”

As you start to make memorable plays for your own personal-highlight reel by unlocking your true potential in school, life and work, Dr. Grant urges you to think about character skills, not just talent (and also be sure to visit Dr. Duckworth’s Character Lab). “Character is your capacity to prioritize your values over your instincts,” Grant writes. “You’ve got to accept discomfort as you make mistakes that are part of the learning process and always be willing to absorb new ideas and information.”

Now that you’ve read the research, take this quiz to assess your own hidden potential.

Conversation Starters

Professor Adam Grant describes character as “your capacity to prioritize your values over your instincts.” What does this mean to you? Would you add to this definition? Can you think of a time when you were able to demonstrate true character?

Why is learning to accept criticism from people we trust essential to unlocking our own potential?

High school can sometimes have its own hierarchy — the cool kids, smart kids, and so on. How might Dr. Grant’s assertion: “Admiring people who start out with innate advantages leads us to overlook the distance we ourselves can travel” help you better navigate that high school culture and unlock your own potential?

In a world obsessed with natural skill,

We overlook longevity and the power of will.

Dr. Grant’s story helps us discuss

How hard work and passion can always help us.

Criticism must be carefully discerned;

Not all who critique have truly learned.

Filter the feedback, and find those who care.

Grow from their words, but make sure it’s fair.

Embrace the “second score,” aim for an A

In how you respond, and make that your way.

It’s not just talent, but character too

That unlocks the potential in you.

Find hidden strengths with every glance,

Give everyone a “do-over,” a second chance.

Make sure to stand out and be you,

Always let your uniqueness shine true.

Dr. Grant’s wisdom is a guide through the craze,

In school, in work, in life’s many ways.

Strong character, values, and drive,

Unlock your potential, and see how you’ll thrive.

Through Perneet’s poem I can act on potential,

Not only the tips, but what’s also essential.

Thanks to Perneet I don’t have to critique,

But rather learn more about what makes me unique.

Dr. Grant makes a point about what it means to shine,

It’s always okay to color outside the line!

Those around you help you learn and grow,

Like Perneet who could be the next Henry David Thoreau!

No talent is ever to big or small,

Writing, dancing, or playing football!

Share the spotlight with others as well,

Find what makes someone else excel!

You only have one life, there’s no time to compare,

Listen to Perneet and find wisdom everywhere!

If there’s one thing I want you to get out of all of my stuff,

It’s that you should always know that YOU are enough!

Thank you, Perneet, for a poem so neat, reminding us

That we are more than life’s rat race; your voice shines true today.

Your work seized this article’s essence for us to discuss;

Raw skill heeds to “power of will” – true passion on display.

Like two nearby saplings, our roots ground us in the same points:

Hurdles will dissipate if you believe in “second scores!”

This article is a real treasure bursting with gold coins!

Our potential is patiently waiting outside our doors!

Fearless artist in this contest, you journey, first alone,

Leaving behind for us wisdom in this comments section.

We join you with our poems; Hope I am not the last one

Who will venture with you in this creative direction.

Doctor Grant said that people have varying intentions;

Critical thinking can help gauge the right social distance.

Perneet, your thoughts about critiques I politely question.

While listening to “those who care,” we can lose persistence.

Say you’re a teen pro-mountaineer yearning for Everest.

Pitching to your caring parents, you wait for their critique.

“I trained and saved, and with your investment, I can contest,

I will climb down safely in time for my college’s first week.”

After your pitch, they will tell you of all the risks involved:

Snow blindness, freezing to death, and gory amputations.

And if you’re not afraid to freeze, they will have that resolved,

Continuing about other risks like dehydration.

And hearing how they care and only want for you what’s right,

Your dream fades because you heard them with the ears of a child.

You should listen to your parents, who are loyal as knights,

But know: caring people can make your dreams become exiled.

Open-minded opinions come from experts in your field.

Present your weak and strong sides but do so with utmost care.

Show true gratitude, and no spite to you will be revealed.

Explore on, until you have sufficient views to compare!

Perneet, you’re brave to write about this topic in this style.

Some people begin to critique those minds which are alive.

But you’re a natural, your unique response versatile.

It blew away convention, and will continue to thrive!

Sometimes I read the word “potential” and immediately feel a sense of dread. Most of the time, “I believe you have potential” translates to “You have talent that we would hate for you to waste” or “You are perfect for exactly what I need you to do.”

I was therefore immediately relieved to hear Grant talk about potential in terms of dedication, hard work, and the unique perspective each person brings to the table. I especially appreciated how Grant talked about the role both person and surroundings play. It is the person’s job to work hard, learn new things, and accept feedback on their work; in accordance, it’s the company, employer, or perhaps the school’s job to cultivate each person’s skill, character, and potential.

The problem is most employers and schools won’t do that. Schools judge the intelligence of their students through tests and rote memorization, which require students to box themselves into a single archetype in order to excel. Meanwhile, job interviews can be simplified down to a formula that people have to be practiced with in order to get a job. When I asked my sister for interview advice, she practically sat me down and explained step-by-step how to answer these questions that she knew they were going to ask. She told me that you just had to get used to it, like it was some sort of test to retake over and over, rather than an actual investigation of skill.

Grant himself admits to falling for these sorts of preconceived notions; of course, he learns from the experience and now advocates for systemic improvements that “create opportunities for those who have been underrated and overlooked.” I one-thousand percent agree. Employers can employ the best of the best if they allow candidates to show off their unique skills. Rather than just training people to do their job as told by employers, employees themselves can also demonstrate the way they do the job, which might be even better than the status quo.

I would even go a step further and say we should implement these kinds of systemic changes earlier. Instead of making school an institution churning out the best test-takers, essay-writers, and memorizers, allow them to be institutions focused on cultivating growth and hard-work. Talent will play a part, certainly, but it should not overshadow other aspects belonging to students, including originality, creativity, organization, leadership, community-building, and more. If we give people the chance to flourish these particular abilities within an academic setting, they become more prepared and able to draw out the “potential” within them. It’s a win-win situation for all parties.

Who gets to define what potential is? Teachers? Employers? Your peers? Grant defines it partially as “character,” or “your capacity to prioritize your values over your instincts.” I will define it as your ability to grasp everything you’ve got and use it to the fullest, even with and in spite of what is expected. Potential should not be a talent you were born with. Rather, it should be something you can acquire, adapt, and train. It should be accessible to everyone, and most of all, it should be a demonstration of you—who you are as a person, who you aim to be, and who you are to your community.

Hello Jade,

Thank you for your thoughtful and insightful comment on Adam Grant’s perspective on potential. Your reflections on the concept of potential and how it is often misunderstood and misapplied was very eye opening for me.

When you described hearing the word ‘potential’ and feeling a sense of dread, you aren’t the only one, many people feel the same way as it feels like a burden or a narrow expectation. Your observations about the flaws in our current educational and employment systems are absolutely spot on. Schools praise standardized tests and that can mess with a students creativity and individuality. For job interviews, frequently following a formula that reward rehearsed answers over genuine, raw demonstrations of skill and potential is baffling. Your sister’s advice on navigating interviews highlights this issue perfectly, interviews are now tests of preparedness rather than a showcase of one’s unique talents and capabilities.

I completely agreed with you when you said ‘we should implement these kinds of systemic changes earlier’. By fostering environments in school that value growth, hard work, originality, creativity, and other essential skills, we can better prepare students for the diverse challenges and opportunities they will face as adults in the real world. Adam Grant’s admission of his own learning experiences and advocacy for system improvements is a powerful reminder that even experts can fall prey to preconceived notions but can also evolve and push for positive changes. As you correctly pointed out, allowing employees to demonstrate their unique approaches to their roles can lead to innovations that surpass the status quo. To explain, this mindset can not only unlock hidden potential, but can also drive progress and excellence within organizations.

When you said that your definition of potential is ‘your ability to grasp everything you’ve got and use it to the fullest, even with and in spite of what is expected’ I was truly inspired. This definition basically summarizes the essence of personal growth and resilience. Potential should indeed be accessible to everyone, shaped by continuous learning, adaptability, and the courage to defy expectations. It should reflect who you are as a person, and your aspirations and nothing else.

Thank you again for sharing your perspective, Jade. Let’s continue to encourage these necessary changes and inspire others to realize and nurture their true potential. This way, we can create environments where everyone’s unique abilities are valued and acknowledged.

Best regards,

Dylan

Hi Jade!

Your story really resonated with me, especially how you described the moment when being part of a team shifted into truly belonging there. That feeling of safety and trust isn’t just nice to have, but it’s absolutely essential for people to step up, take risks, and show their best selves. Reading your experience reminded me why I’ve become completely hooked on the idea of psychological safety: the foundation where real potential can grow.

Dr. Grant’s “rotten apple” story from the article really hit home for me. The way he talks about creating a space where people feel safe enough to speak up is, in my eyes, the secret sauce behind unlocking hidden potential. If someone feels like they’ll be judged or shut down, why would they ever take the chance to try something new, let alone accept feedback or admit mistakes? That’s why I dove headfirst into Dr. Amy Edmondson’s work. She’s the leading expert and guru on psychological safety and her concept of “interpersonal risk-taking” perfectly sums it up: people need to feel that their voice matters and that they won’t be punished for stepping outside their comfort zones. What is actually so funny in my opinion is that as I was reading her book, The Fearless Organization, a few weeks back, she came out to speak at Wharton to speak with Dr. Nembhard, a distinguished professor of Healthcare and Management. It was incredible to hear her unpack how organizations can shift culture to welcome failure—not as a stigma, but as a necessary step toward growth. It really reframed how I think about my own leadership and teaching roles.

Speaking of which, I’ve been teaching dholak for four semesters now, working with a mix of middle schoolers and adults. It’s not a “team” in the traditional sense, but psychological safety is everything there. When you’re sitting between kids and grown-ups, sometimes it’s tricky to give feedback without making someone feel exposed or discouraged, especially the younger kids who are just finding their confidence. Creating that safe space where they know mistakes are part of learning makes critiquing easier and more effective. Everyone is willing to listen and improve because they don’t feel threatened or embarrassed.

The same goes for my robotics outreach, which I’m really proud of. I’ve helped manage two sister teams and mentor younger students across elementary and middle schools. Plus, I’ve been part of huge events like Moonday (an annual celebration held at Dallas’ flight museum), where we engaged with almost a thousand kids and parents. We don’t just show up and talk about robotics; we spark excitement through hands-on activities like launching Coke cans with our can blaster, rides on our homemade hovercraft, coding sumo robots, and 3D printing keychains. But before any of that can work, we focus on building psychological safety—making sure kids feel curious, supported, and free to ask questions without fear of looking silly. We also talk to parents, giving them the resources to help their kids dive into STEM. It’s about creating an environment where potential is carefully nurtured to help individuals feel safe and confident enough to take risks, ask questions, and explore new ideas. Without psychological safety, it’s really hard to get kids genuinely interested in STEM or to encourage them to dive deep into their passions. If the environment feels judgmental or threatening, kids won’t feel comfortable stepping outside their comfort zones, and their curiosity and growth can easily stall before it even begins.

Reading your story and Dr. Grant’s ideas reminded me that no matter the setting—whether it’s a music class, a robotics workshop, or a classroom—psychological safety is the bedrock for unlocking potential. When people feel safe, they innovate, they lead, and they surprise themselves with what they can do.

Thank you for sharing your experience, Jade. Your words gave me even more motivation to keep building those safe spaces where others can find their strength and confidence to shine, no matter where they start.

Why do we exert ourselves? Is it for personal benefit? For others? Is it just for money? Oftentimes, the answer to this question can be summed up by one word: results. Students study so they can pass their classes. Adults work so they can provide for themselves and their families. And people pursue their passions because it makes them happy.

However, despite our common goal to achieve results from our actions, our actions often yield varying results. If I need to study for 5 hours to pass my math test, that doesn’t mean that all of my classmates will also need 5 hours to pass the same math test. For some, it may take 2 hours; for others, it may take 10 hours. Interestingly, the same principle applies to our personalities and opinions. For example, I may think that spiders are frightening (which they are!), but someone else may be totally fine with them. Or, I may think that a hot dog is a sandwich (which it obviously is!), but someone else may totally disagree with me.

This principle of human individuality is accurately portrayed by Dr. Grant’s journey from “the worst diver on the team” to an All-American and the story of an antique apples sales representative. While Dr. Grant didn’t possess the innate diving talent to excel when he first started, he had the grit and love for the sport that ultimately allowed him to succeed. And while the sales representative was lacking in social skills, he still shined with his creativity.

Our uniqueness is what leads Dr. Grant to call for us to break the mold, which I wholeheartedly agree with and is something I live by as I try to achieve the result of defining my individuality.

Hi David,

I enjoyed reading your comment about your outlook upon the reason for individual’s exertion and endeavors. I really do agree with the last sentence, where you mentioned that ‘our uniqueness calls for us to break the mold’, and it made me appreciate my own identity of uniqueness.

Going further, I think not only our uniqueness, but also our vision motivates us to put in the efforts on a particular matter. Personally, I study business because I have a vision of saving people that needs help with my product or service, and becoming a founder of that company to actualize and operate products so that I can be sustainable, both environmentally, socially, and economically.

This vision that I have may sound like a result, where I make a splendid product. However, the vision is covered behind the product, and the endeavors that I have put into studying business.

Extending from your appreciation of individual’s uniqueness, I believe that once we discover our own vision, it will lead us to a new realm of possibilities and results.

“As long as you work hard, you can achieve whatever you want,” said my dad, an immigrant from China. It is always comforting to see the adage, “Hard work beats talent when talent doesn’t work hard”, proven right: in this case, it was Grant’s journey from being “hands down the worst diver on the team” to an All-American diver. However, society has come to a point where we are so fixated on what we define as raw talent that we lose sight of the capacity to grow. Still, Grant’s story and research into finding the best environments conducive to unlocking one’s potential makes me hopeful. He offers practical approaches for people to grow and shine. For example, the “second score” method allows one to keep calm in the face of criticism and to critically reflect on the feedback rather than simply taking offense. A key comment brought up was the hidden potential in future employees. Grant’s anecdote about the introverted salesperson demonstrates the limitations of traditional interview processes and the value of giving candidates opportunities to showcase their skills in relevant contexts. It is so crucial to the future of companies that motivation triumphs over charisma in the search of a perfect candidate. Even now, there are so many obstacles obstructing the paths of future innovators and workers. Still, I am hopeful because articles like these provide an optimistic message that with awareness, more and more opportunities will open for those who put their blood, sweat, and tears into their work.

Dr. Grant’s inspirational tips and comments on the importance of finding the greatness and talent that lives within each and every one of us (whether we realize it or not) has led me to think about how my potential has impacted my past, is impacting me currently, and will impact my future.

When I think back to as little as one year ago, I can recall multiple times where the decisions I made led me to a greater sense of self discovery. For example, last fall, I decided to step outside of my comfort zone and audition for my school’s play. I didn’t know anybody in the theater program, I was actually kind of embarrassed that I had decided to try out, and I had little to no acting experience. Fast forward to now, where I not only got a role, but the experience was incredible. I have met some of my best friends in the program and have grown immensely in my confidence, public speaking ability, and willingness to try new things. Had I never been willing to give theater a try, I wouldn’t have been given the opportunity to “sell” what I saw as a “rotten apple” and turn it into the gift of theater, that has opened my eyes to a greater sense of potential I can exhibit.

As I look ahead to the future, I can’t help but to use the “learning to accept criticism” mindset, introduced by Dr. Grant, to help my potential growth flourish as I discover more about myself, others, and opportunities on my life journey.

I think many people just don’t try to do things other than they usually do just because they think they don’t have the potential for it. I was also one of these people. I used to play tennis but I think I had no talent for it. Even after playing this sport for quite sometime, I gave up because I saw other newcomers easily getting where I am. It felt like I was not improving and then a last decided to quit the sport. But later I regretted the decision when I realised that with determination we can do anything. Some people might be faster to learn somethings from others. But with hard-work and determination we can definitely excel in any field regardless of talent. And stories like this just prove that belief. Work hard till its printed in your DNA. If you don’t have the talent, then create it. In today’s world it is very necessary to look behind outward appearance. There is all stars and shimmers around us with all the different buzz and success stories on the internet. People just showing-off things which in reality they don’t have. Don’t just get demotivated or awed just because you see others in a Lamborghini and you in a Honda city. Work hard towards a goal without caring about others. I although didn’t start tennis after this realization but I still worked hard in academics especially in subjects which I was not good at and even in many things. Although I don’t have many medals or trophies. I am recognised for hard work my friends and classmates. This change motivated me further to work-harder until i became totally disciplined. I stopped going for the rank 1 in whatever I was doing after realizing this for show-off which maybe not conscientiously but conscientiously I was doing and participating in competitions to get rewards for feeling accomplished but instead started doing this to constantly improve and see how far I have come.

Before COVID, I attended countless piano competitions, auditions, and recitals. Because of quarantine, I stopped. After COVID, when I arrived at 7th grade, I got into a new school and decided to perform again, this time at the school’s Arts Day. Especially because it was the first time after a long break, I was extremely nervous. I played Chopin’s “Grande Valse Brillante” and ended up making many mistakes. In 9th grade, my mom encouraged me to audition for Arts Day again, this time for Chopin’s “Barcarolle.” I had improved my piano skills during these two years of hard work and extensive practice, and I performed again. By the time it was my turn to go on stage, I felt distinctly less nervous. The performance wasn’t perfect, but I was expressive, and, most importantly, I enjoyed it. I felt deserving of the audience’s applause; not because of my performance itself, but because I knew it was a step towards being more comfortable in a situation that, two years ago, I was not.

Dr. Adam Grant wisely says, “Admiring people who start out with innate advantages leads us to overlook the distance we ourselves can travel.” I resonate with this since, in my musical journey, sometimes I used to become frustrated because I thought that others were better than me, causing me to overlook my own passion and potential. I would always wonder why it was so hard to stand out. Like Dr. Grant’s diving story, I kept practicing music, through failure and success, through lows and highs, all because I simply love music. Piano came into my life when I was five, and it has been a very, very rocky journey. With all the support I have from my parents and teachers, I continue to learn music despite all the sinkholes and landslides life throws at me. I have almost given up many times, but I am sure that would have been a major regret. For this, I am thankful to my own efforts, my perseverance, and encouragement from all people around me.

I agree with Dr. Grant’s interesting take on potential and talent. His article made me think more about what potential is, and I can describe it as more individual: it’s creativity, perseverance, grit, open-mindedness, the ability to become my dream self. However, when I think deeper, I think potential is far beyond what is mentioned in the article. From my own experience, music allows me to realize the potential of becoming an efficient problem solver and a focused learner in every field I’m in. Most importantly, it will accompany me as the best lifetime friend and joy. That’s the kind of special potential music has brought out of me. Not only do I love music and playing piano, I also love learning theory to help me compose music. Whenever I play music, it’s like talking to my inner self.

According to the quiz, my place for improvement is seeking discomfort. I have been working hard on doing so, especially this year. I attended the theatre practicum elective, where I improved at performing and learned to project my voice. I joined the new parliamentary debate team and attended two tournaments. In English class, for our speech presentation, I felt the skills I learned from theatre and debate come to fruition. Although I couldn’t audition for the second Arts Day of 9th grade due to schoolwork, I hope to do so next year, showing off even small rises in confidence, and be able to look in the mirror to say: I’m not the same.

I truly enjoyed reading your comment. As I was reading, I quickly searched Chopin’s “Barcarolle” on the internet and it’s such a great piece! Peaceful, tranquil, and graceful. I’m guessing you surely have put in a lot of effort in those two years. Personally, I play cello so I could quite resonate with you. To talk about myself a little bit, I’ve been playing cello since I was in 3rd grade, and just like you, I’ve had a break during the COVID period and a lot more before because my family was moving a lot into different environments. So playing again after COVID felt like a huge challenge for me. I’ve been “decent” at playing cello since I started it and compared to other kids, people around me always used to say I had that “potential”. Before COVID, I was playing and practicing well. I’ve always used to be the first chair of whichever orchestra I was part of and I enjoyed the music I played. At one point in my cello journey, I became arrogant as I accomplished things without huge obstacles and once even genuinely thought that I was one of the “people who start with innate advantages”.

Thinking now, I’m indeed very embarrassed with myself for thinking that. After COVID, at my new school, I joined the advanced orchestra and even though my skills have become a lot rusty, I was still the first chair– Until I entered high school. In my Freshman year, I auditioned for advanced orchestra in high school which I thought would be easy and that’s when I experienced my first ever major failure. I was too lazy to practice and just a few days before the due date, I crammed and ultimately failed. It was a big shock but it wasn’t big enough for it to make me think of giving up because I had the excuse of not practicing and having that long break. Then in my Sophomore year, I auditioned again with proper preparation and got in this time. But another big surprise was waiting for me. I wasn’t the first chair. Indeed, I was in the second last row. Now this was too big of a surprise. I was devastated and quit cello for a few months(I only practiced in an orchestra). When I actually met people who were better than me in real life, I didn’t have the…I don’t know how to express this, but the willpower to accept that and continue practicing to become better. So that’s why I was surprised by your perseverance to continue when you encountered your failure and I respect that. Whenever I see people who have this quality of accepting failure and criticism early on, I admire them deeply because I couldn’t do it until now. What I realized about “potential” from my failure is that potential will forever stay as just “potential” unless you try to bring it out to life. It might be quite obvious for some but I learned this as a sophomore. In my case, my potential wasn’t hidden and by just relying on that fact, everything goes well until you realize that it is not enough to just have more potential than others.

You might be wondering how I’m doing now. I’ve joined multiple music festivals and met even more talented people. I, fortunately, didn’t quit and am continuing on my journey to become the first chair again. Hopefully, by senior year, I will get back… and humble myself and others.

While most average of average horseback riders eat dirt (fall off the horse) at most ten times a year in the beginning of their career, I have eaten dirt nearly three hundred times throughout my nine years in this sport (I haven’t broken any bones yet but knock on wood). So while Dr. Grant may have been the worst diver on his team, I was probably the worst horseback rider throughout my entire city. But just like Dr. Grant, I love this sport more than anything. Ever since I could walk, I would plop myself onto the horse plushies and sit there all day. So for my seventh birthday present, my mom let me finally ride my first real horse named Luna. This may have been her greatest regret to this day, but it was the beginning of the best experiences of my life.

Within the first couple of rides my lack of athletic talent stuck out like a sore thumb. One of the first steps in learning how to horseback ride is to practice posting at the walk, the movement of sitting in the saddle and then standing back up. However, as you leave the saddle, you need to maintain balance to stay with the movement of the horse. I stood up and my legs immediately began to quiver due to my lack of muscle. As Luna saw a tuft of grass along the fence, she turned right to eat it. Although the motion was painstakingly slow, my inertia caused me to sway left. That’s how I ate my first mouthful of dirt.

Before my coach could run over to check on me, I stood up and started laughing, a mixture of dirt and blood from a split lip spewing out of my mouth. At seven years old I had no idea what muscles even were, but I took my coach’s advice and began eating more eggs and running more often. My balance eventually improved, but a whole new set of problems began as I started to learn showjumping. Weak core strength and slow reaction times were just two of the never-ending list of skills needing improvement.

The barn that I ride at has a system where you start off with a coach who teaches you the essential skills of flatwork and the basics of showjumping. Then another coach takes you on and helps you refine your skills in showjumping. After a couple of years, most riders look towards joining under the mentorship of this one particular coach who guides each of his students to being competitive at the national and international level. However, this coach only instructs students who he thinks can keep up with his strict lesson plan, where everyone trains around courses of similar technicality and height. I was certain I would not be accepted into his program. Even though I spent everyday training both on and off the horse, I thought I could never reach the level of those riders who were gifted with athleticism.

So when this coach told me that he was looking forward to our first lesson together, I just awkwardly spurted out the word “why”. He told me about how he had seen my dedication to this sport never wane despite facing numerous challenges (The entire barn knew about my infamous fall count). Yet at this moment, I suddenly started having doubts. I asked him, “What if I can not keep up with the other riders?”

But, he just responded with, “I will help you get there. I know you can make it.” Later that week, I figured out what he meant. He had provided me a routine schedule with training modules specific for equestrians as well as a few horses for me to exercise daily in preparation for the summer camp. Additionally, once a week for the next three months, he would inspect my skill improvement with a “riding test,” where I would work on flatwork and receive feedback afterwards. As my coach says, “Showjumping is just flatwork with a couple obstacles.” If a rider can maintain the perfect balance and rhythm of their horse, those obstacles will never be a problem.

I will be grateful for his belief in me for the rest of my life as he gave me the opportunity to grow my skills within this sport to a level that I thought I may never reach. Even though I wasn’t talented and could barely hold my body upright as I first started horseback riding, through a combination of passion, self-discipline, and many supportive mentors, I did eventually reach those aspiring goals. As I won at my first international level competition, I shed tears for the first time in my seven years of horseback riding. I knew that I could fall off in my next round, but I also knew that these would become lessons for my coach and I to analyze and improve from.

So within sports or any other part of life, I make sure to celebrate any successes, whether big or small. As progress can often look like a maze, those moments keep me motivated to continue pursuing the dream that started as I napped besides my horse plushie, Luna (I later named it after the first horse I rode).

I can remember my first day at my tennis classes. I was 13 years old, terrified, and insecure, but decided to be the best. I could barely hit a volley correctly, I uncomfortably moved through the court, and after a year, my serve was still pretty weak and bulky. But I am glad I could relate to this article since it meant that I had a coach who helped me stand out and improve. Ricky, my tennis coach has observed me in the ups and downs of my tennis journey, and most importantly, he taught me that things are not earned for free, he helped me unlock my potential in ways that I hadn’t experienced before, and especially at a time where I felt I had no talent for the sport. Ricky taught me that the only limit is my mind, and if I wanted to improve, I had to put those talent constraints aside, just as it happened for Adam Grant. He helped me to challenge myself to work harder on my volley and serve and discovered my potential in my backhand and forehand. He criticized me, and scolded me, many times, but with this, he taught me that criticism is good, especially when you don´t want to hear it, and mistakes are crucial because they are the only way to shape your experience and learn from it.

I felt identified with this article because it was during that time when I began playing tennis, that I realized that innate talent is not everything. I have to agree with Diana Drake, that in a world that is obsessed with “innate talent” we end up forming a fixed mindset, and we fail to look at the range of skills that we could learn. Most of the tennis superstars that I used to look up to, and thought about as being naturally gifted, were the result of years of hard work, grit, frustration, and learning from their mistakes. I realized that unlocking potential was not about being talented or gifted, but something you actively work for. That made me find Adam Grant’s words full of wisdom when he said “admiring people who start with innate advantages leads us to overlook the distance we can travel.” It was only after I switched my mindset that I was able to unlock my mind, break free from false constraints about talent, and build a growth mindset with the help, inspiration, and constructive criticism from my coach rather. Although it was not easy at first to get used to having someone constantly criticizing you and correcting you on something that you love, you learn to change the way you appraise it, so it can become constructive and helpful. As Adam Grant expressed in this article, I learned how to get a perfect score on accepting and processing criticism.

Lastly, this beautiful journey that I have been immersed in with tennis transformed my identity for good and got me some experience in the mindset needed to become good at a sport. This experience helped me to become more self-aware, compassionate, and excited to help my friends on this journey. I remember especially a girl, who is around 13, the same age as when I began playing. I remember her fondly because she reminds me of my younger self, with constant doubts about her capacities, constantly contemplating the idea that she might not be talented enough, and fearing failure. I have been helping this girl with her journey, focusing on where she is already skilled to work from there, helping her to realize that failure and criticism are important parts of learning, and since they will inevitably happen, we can only change how we react to them. And helping her realize that greatness does not come from giftedness but from grit, hunger, and challenges.

As Adam Grant said, it is not about breaking people to fit in the mold but helping them stand out with their already-known skills. It is about character skills, not talent. Character is your capacity to prioritize your values over your instincts, and as we are looking to find potential in ourselves and others, we should accept discomfort as we make mistakes, and be willing to absorb new ideas and information.

The article above mentions Dr. Grant’s book Hidden Potential and its quest to help everyone find their hidden potential. He explains the importance of receiving criticism from the best sources: people who are knowledgeable, people who know you well, and people who want you to succeed. Receiving criticism well is one of the most important skills for self-improvement, and knowing how to take criticism has helped me improve as a badminton player.

I started playing badminton later than many of my peers. At my first tournament, I played one match before I was eliminated. I lost 21-3 and 21-5. It was a devastating defeat, and I felt hopeless.

On the way home, I told my father, “I don’t want to play badminton anymore.” I didn’t think I could “make it” in the competitive field of badminton.

My father kindly replied, “Keep at it. If you continue training, you’re going to win eventually.” I’m glad I didn’t quit badminton; it’s my biggest passion now.

Two years later, our badminton club hired a new coach. Coach Toby specialized in mixed doubles and he volunteered to play with the junior players outside of class time. He had a passion for badminton and was a self-improvement guru. For my birthday, he gifted me the book Grit by Angela Duckworth and introduced me to many influential self-help books, including Dr. Grant’s Hidden Potential.

I’m grateful to have read self-improvement books like Hidden Potential as it has not only kept me going in my badminton journey but is has also taught me ways to improve. In the article and in his book, Dr. Grant states that we need a filter to determine what criticism to listen to. Feedback from those with relative expertise, knowledge about you, and the intention to help you is worth listening to. When I played with Coach Toby, he provided feedback on my strategy and playstyle. Coach Toby specialized in mixed doubles, so he was an expert on the preferred shots to play in certain situations. As my coach, he knew my playstyle and wanted the best for me. For me, learning to accept helpful criticism was the key to improvement.

After another three years of training, I won my first nation-wide badminton tournament in mixed doubles. Five years ago, when I lost in the same tournament first round, I could never believe that I would go on to win one of these tournaments. The supportive people in my life have helped me realize my potential and urge me to never give up, even when I begin to doubt myself.

I don’t have the typical “potential” that most coaches look for. I’m lucky to have a great coach that believed in me and introduced me to the realm of self-help books. I’m still not the best badminton player, but I’ve come a long way from when I started. Books like Dr. Grant’s Hidden Potential have given me hope. Thank you, Dr. Grant, for rejecting the system of potential and giving me hope to reach new heights.

I think Professor Grant’s definition of character is spot-on. Character is acting despite difficulties and failures. Even if you don’t feel like doing something, you do it because it’s important and you committed to it. It’s not easy—you need to be resilient and consistent. I’ve been working on strengthening my character for a while now. It helped me achieve successes, like when I studied every day for months for the Entrepreneurship Olympiad. I built discipline, even with temptations to slack off and return to my comfort zone. In the end, it paid off, and I don’t regret it. Hard work beats talent any day, and I believe you can do anything if you’re committed enough.

Another crucial trait is the ability to accept criticism from others—but not just anyone. As Dr. Grant said, many people don’t necessarily want what’s best for you or may not know the full situation. But those close to you usually offer constructive criticism. If you listen instead of shutting it down, you can improve fast. We can’t spot all our weaknesses on our own, and that’s what holds our true potential back. I’m still working on this because, honestly, I often feel too closed off to criticism.

When I started playing on the school basketball team in 9th grade, I was the worst player. I practiced on my own, watched YouTube videos to improve, and showed up every single time. Now, nearly three years later, I’m proud to be one of the best. If you focus on how others perform, it’s easy to get discouraged, feel like you’re not progressing fast enough, and quit. In the long term, comparing yourself to others can help, but the key is to aim to be better than you were the day before. That’s the path to victory.

From sticking with diving no matter how hard it was to misjudging someone’s potential based on first impressions, Dr. Grant’s Hidden Potential is the kind of honest, unfiltered reminder that every teenager needs to hear. The idea of grit — pushing through obstacles, giving something your all, refusing to quit when things get tough — is something people talk about constantly, but very few actually live it the way Dr. Grant did. His diving story really stuck with me because it made me think about all the times I gave up when something felt too hard or out of reach. Could I have gotten better if I’d kept going? Or would I just have wasted time on something that wasn’t right for me?

That question, whether to keep pushing or to walk away, reminded me of another article I read on Wharton’s site: 5 Tips to Help You Know When It’s Time to Quit. In her conversation with Dr. Grant, Annie Duke points out something people rarely say: “quitting will get you to where you want to go faster”. Sometimes we stay stuck doing things that no longer help us grow just because we’re scared of how quitting might look. Reading both Dr. Grant’s and Duke’s ideas made me realize that real growth is about more than just grit, it’s about knowing when to switch and put your energy into something that matters more.

Hidden Potential shows the idea that talent isn’t something you either have or don’t, it’s something you build over time. Dr. Grant shows that it’s less about where you start and more about how willing you are to keep learning, take feedback, and push past your limits. And as long as you have a clear goal and can see yourself getting there, sticking with it makes sense. But when that goal no longer feels right, like Duke says, sometimes letting go is the best thing you can do for yourself. What matters most is staying open to growth and not being afraid to change direction when you need to.

Personally, I don’t believe in either talent or potential. Innate advantages sound like an excuse for people who are exceptionally good at a field, when we don’t get to see all the hard work that goes on behind the scenes. Similarly to Grant’s story about high school sports, I used to be among “the worst” in my dance studio. However, through practice, practice, and more practice, I was recommended for the high level dance class last year. I didn’t have a particular knack for dance—it was through my passion and dedication to improve each move, each class, each performance, that made it possible for me to become an advanced dancer.

I also started volleyball for the first time in my freshman year of high school. Honestly, at 5’2”, I am not the ideal height for a hitter. So, I had no talent or potential based on my physical height. However, I worked hard. I went to the ballpark everyday after school to practice, and used all my free time in the backyard to practice drills. Soon enough, within the span of three months, I was able to receive fast balls I couldn’t before, spike more precisely, and become a more confident athlete. Even now, I am currently practicing everyday this summer to prepare for the upcoming season.

Although I started dance and volleyball as a complete newbie, I’ve learned that hard work and persistence are requirements to be great in any endeavor and that success is not limited to innate potential. Don’t let talk of talent and hidden potential hold you back from what is possible!

Just like Adam Grant was “hands down the worst diver on the team,” I had, hands down, the worst natural conditions for a dancer in my ballet class. My ballet teacher made sure that I acknowledged my talent constraints early on. She was very competent in her field and had known me since I was a child, so filtering criticism wasn’t really the issue, but accepting it and moving forward was. I was often choking back tears after hearing various comments related to how my body was developing as I was hitting puberty and how it affected my performance. I remember fighting mental battles before every ballet class, but still attending every day. This is how I personally learned what grit looked like. I also acknowledged that although I kept hearing harmful comments, my ballet teacher never stopped pushing me forward with my training. I learned how to cope with my “lack of talent” or heavily romanticized “gift” by being truly persistent. In the end, I was chosen to perform on stage, even though my range of motion and body were not traditionally “ideal” in this innate-advantage-obsessed world. My story, as well as Adam Grant’s, proves that if we combine persistence with accepting criticism and being motivated enough to push forward no matter what, everything is achievable. That is why, as a future employer, I will look for people who embrace those qualities instead of just being gifted. I truly believe in giving people a chance to unlock their personal potential while helping them “put their best foot forward.”