Leadership Lessons from the Thailand Cave Rescue

Few experiences illustrate true management principles as profoundly as the Tham Luang Cave rescue, an 18-day saga that played out over recent weeks in a forest reserve in northern Thailand. Twelve boys, ages 11-16, and their soccer coach braved hunger, thirst, darkness and despair inside the flooded cave system before the last of the group was rescued on July 10.

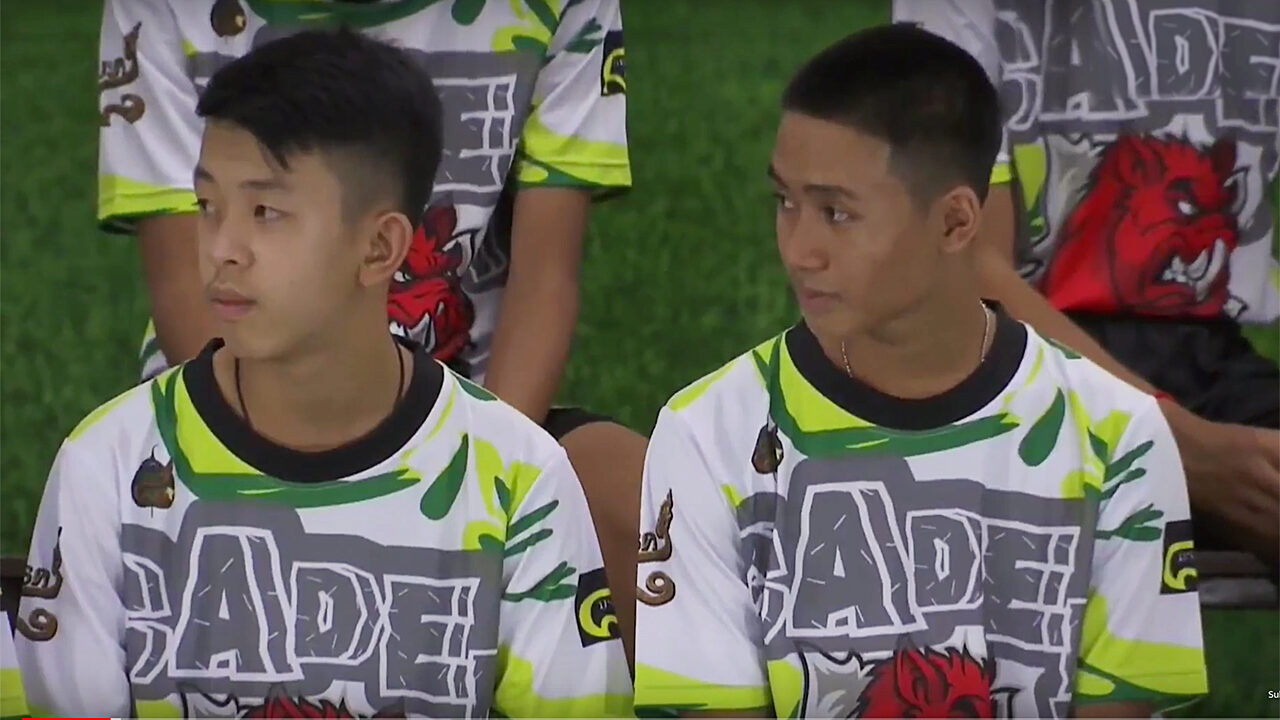

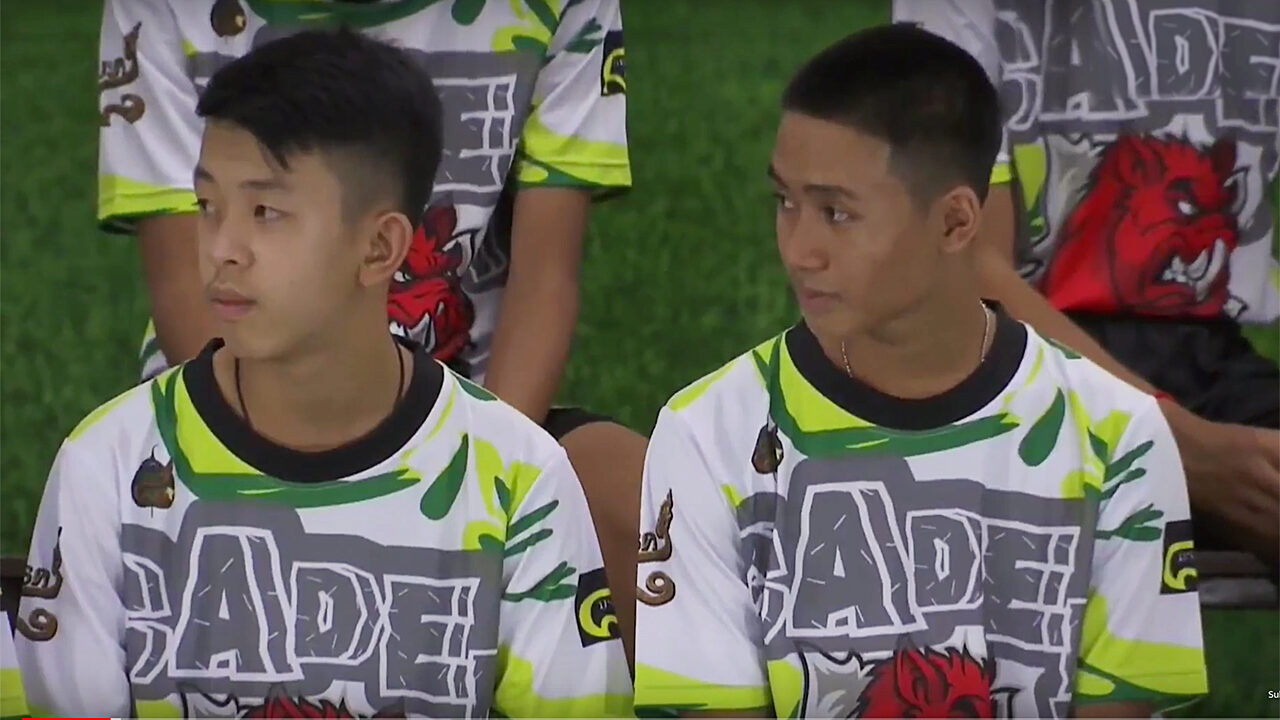

On July 18, the Wild Boars teammates and their coach walked out of a hospital in Chiang Rai city, healthy and free at last from their ordeal. During a press conference, the team talked about their struggles inside the cave. “After two days we started to feel weak,” said one of the teen players, explaining that they had no food, but that they did find a trickle of fresh water to drink that was streaming off a rock in the cave. We dug to try and find a way out for days, one of the boys added, and they had to use their one flashlight “economically.”

In addition to illustrations of grit and survival, the cave rescue holds exemplary lessons of leadership and large-heartedness, according to Wharton management professor Michael Useem and Andrew Eavis, a U.K.-based president of the International Union of Speleology, an organization devoted to the study of caves. They discussed the salient takeaways from the rescue mission on the Knowledge@Wharton show on Wharton Business Radio on SiriusXM channel 111. (Check out the Related Links in the sidebar to listen to the podcast of this article.)

The rescue effort was a carefully coordinated strategy involving multiple groups, including dozens of the world’s best divers and cave experts; some 10,000 volunteers; individuals and organizations that brought in pumps; and farmers who willingly allowed pumped out water to inundate and kill their crops. The Thai government contributed funding as well as medical, logistical and administrative support. All that happened as the world watched the rescue effort unfold by the minute, brought to them by the roughly 1,500 journalists who had descended on Mae Sai, the town nearest to the caves and on the Thailand-Myanmar border. Elon Musk, the billionaire founder of Tesla and SpaceX, brought a mini-submarine to the rescue effort, but it wasn’t used.

It began with an urge for an extra bit of adventure. On June 23, the 12 members of the Wild Boars soccer team and their 25-year-old assistant coach strayed too far beyond tourist limits at the Tham Luang Nang Non cave in northern Thailand. It was the wet season, and torrential rains flooded the six-mile maze of caves, forcing the boys and their coach to move further inside to an elevated, dry place. Rescue teams found them 10 days later, after using maps provided by Vernon Unsworth, a British spelunker (or cave explorer) who knew the Tham Luang cave system well. Incessant rains prevented an immediate rescue, which eventually began on July 7.

Brain Power and Muscle

Over the next four days, a team of 18 divers that included Thai SEALs, and British and American divers, rescued each of the trapped individuals one by one, although they were emaciated and had minor health issues. “It was a matter of muscle and brainpower,” said Useem, who is also director of Wharton’s Center for Leadership and Change Management, quoting a news report on the rescue.

While the equipment used in the rescue made up the muscle, Useem said the brainpower came from people such as Narongsak Osatanakorn, the former governor of Chiang Rai province, to whom the Thai government entrusted the task of coordinating the rescue effort. Osatanakorn’s prime tasks included leading the 10,000 rescuers onsite to a common strategy, and “he brought discipline, organization and decisive decision-making,” he added.

Eavis described how the young men got into progressively deeper trouble inside the cave. “What we had was a tourist cave going for something like half a mile…. Beyond that, there were two small passages, and these boys and the coach initially got over-adventurous and they went beyond the show cave and up one of these smaller passages. When they were up there, a wall of water came down…. Some of these boys knew the cave — they’d been in there before — so I suspect they knew that there was a high-level area [further in] where they could go to stop themselves from drowning. And that’s where they were for two weeks in the end.”

Tragedy had struck a day before the rescue effort, when Saman Kunam, a retired Thai navy diver, died from oxygen deprivation as he went about setting up oxygen tanks inside the caves for the benefit of the trapped and the rescue teams. “Aside from that terrible, terrible loss of life, this is a miracle,” said Useem, noting that initial estimates had said it would take up to four months to complete the rescue.

Three-pronged Approach

According to Useem, the rescue effort relied on a three-pronged strategy. One was the Thai government that sent money, supplies, Army personnel and other resources. The second was Osatanakorn and his disciplined leadership. Useem quoted Osatanakorn as telling the volunteers, “Anyone who cannot make enough sacrifices can go home and stay with their families. You can sign out and leave straight away. I will not report any of you. But for those who want to work, you must be ready any second, and then just think of them as our own children.”

The third prong was the group of 13 young men that were trapped deep inside the cave. Although the coach, Ekapol Chanthawong, has been criticized for leading the boys too far inside the caves, he encouraged them to stretch the limited food they had and battery life left in their flashlight, and to stay positive. “The government, an onsite leader and then [the trapped people] inside the cave pulled it together,” said Useem.

Coach Chanthawong also taught the boys to stay calm with meditation, according to a Washington Post report. A Buddhist monk who knew Chanthawong sent him a note inside a plastic bottle through one of the divers who went inside, the report adds. The note read: “Be patient. Try to build your encouragement from the inside. This energy will give you the power to survive.”

Useem recalled the Copiapo mine accident in Chile in August 2010, when a cave-in trapped 33 miners, and they were rescued after 69 days. Like the Thai soccer team, the miners spent their time in near total darkness as they were confined 2,300 feet below the ground. In that situation, it was foreman Luis Urzua who kept the miners focused on survival.

Useem said Chanthawong helped the boys find potable water as well. “Apparently, he demonstrated to the boys that if you were very careful coming up against a wall, there was a bit of a water drip and if you got your tongue out, you could actually get some fresh water,” he said. “The rescuers on the surface or at the mouth of the cave couldn’t have done a thing if they got there and the boys had not survived.”

Eavis noted that the age difference between the assistant coach (who was 25) and the boys (aged up to 16) was small. “I don’t know how much control the coach had over them,” he said. “But we know how much he was instrumental in them going in and how much he was instrumental in planning their survival.”

Useem saw the crisis as a testament to the leadership reserve in Chanthawong. “He got them into the mess to begin with, but once there, he held it together himself. People who are under dire circumstances with a leadership responsibility have to step forward and exercise it. And the reports are that he was able to do that indeed.”

The divers had among the most challenging of tasks, but fortunately had to deal with minimal bureaucracy. “The cave divers did the sharp end,” said Eavis. “But they had a great deal of help and a huge number of people facilitating that. The Thai authorities were not very slow at paying the airfares and getting the teams there. And then once they realized what the situation was, they facilitated what the divers wanted. It’s a different world when you’re diving underwater underground. [It’s] crawling along tight passages, full of water … and it is not something that many over-water divers are very comfortable with.” It helped that underwater cave exploration was a hobby for those divers, he added.

Technical Feat

Managing the technical aspects of the rescue was another feat, said Useem. He pointed out that one of the four Thai SEALs who went in and stayed with the trapped soccer team was also a physician. The rescue team had to plan how they would go about the evacuation of those that were trapped, which they ultimately made way for by pumping out about a half billion gallons of water, which he described as “a huge engineering problem.”

Pumping out that water into neighboring Thai farmers’ fields also facilitated the rescue, Useem said, noting that the farmers declined to accept compensation that the Thai government offered them for crop losses. “When there is an emergency like this, people step forward expecting no compensation, no material consequence because of the circumstances,” he added, commending especially the divers who participated in the rescue. “And that was demonstrated in spades here as it was back in Chile.”

Eavis pictured the situation the very first set of divers must have faced as they went deep inside the cave. “It’s incredibly dark. It’s something that you need to experience for a while to really understand; literally, you don’t know whether your eyes are open or closed and you suddenly find that the dial on your wristwatch is incredibly bright and that is pretty extraordinary,” he said.

“The first very important thing was two divers getting through to start with, and I know they had a real struggle to get through because they were fighting against the current in the water,” Eavis noted. “They almost gave up, but when they did get through the first time, they took a big rope with them and secured it through so that they could then pull themselves through using the rope on subsequent journeys. So that first trip was the really important one. If they hadn’t made it, and if the currents had been a bit stronger or the passage had been a bit smaller, or they hadn’t possibly been quite so brave, the lads would have still been sitting there.

Did you watch the 18-day Thailand cave rescue story unfold? Did you identify with the plight of the Wild Boars soccer team, many of them high school-aged? What went through your mind as you were tuned into their story? Could you relate or even empathize with their situation?

Take a moment to review the various ways that people stepped up as leaders and supporters during the Thai cave crisis. Which leadership takeaway resonates most with you and why?

How has this story of rescue and humanity impacted the way you think about crisis and survival? Has it changed your perspective? Enlightened it? Where does ‘heart’ fit into all of this?

Hy, I’m Ícaro Bacelar, a High School student from Brazil. Unfortunatly, I didn’t get to watch the rescue, but I was keeping up with it by hearing about in BBC News podcast. I’ve never been in a similar situation, I mean, I was never trapped or locked in anywhere (and I give thanks for that), so I don’t know exactly how does it feel. But I’m sure about how terrible it was, the feeling of not knowing what will happen in the next day, if you and your comrades will be ok or not… In this scenario of chaos and despair, a figure of a leader is more than important in order to keep the calm.

This story did not change my mind, it just reinforced a point I already belived in: that humans can be incredble and show a great strenght when it’s needed. Also, “heart” fit in many points in this event, mainly if we’re talking about courage and generosity, due to the great bravure that all the kids and the rescue team showed and the wonderful acts of the kid’s coach, which taught them techniques to maintein the calm and used the least supplies possible.

It was incredible to see the effects of it outside the cave: the support offered by the government, of Thailand and other nations, and the amazing response of the population, that did not panic, something “comum” when a tragedy occurs. A pretty thing that we could see in this rescue was the called “Brain Power and Muscle” combination, in which many researchers, “drivers” and high tech equipaments worked together to salve the Wild Boars.

Hi Ícaro. Thank you for your comments! It’s interesting to me that this story points out many leadership roles in helping to rescue the boys, but it does not consider the contributions of the boys themselves. I know not much is yet known about the dynamics inside that cave, but I’m quite certain that we must be able to learn some lessons from the students, as well, and that they were not just victims, but also leaders. The mere fact that they survived suggests they have strong qualities. Do you think we can learn anything from these boys, who are ages 11-16?

Of course! These boys actions are a whole lesson of self control and mutual respect. The fact that they did not turn that horrible situation in something really chaotic, but insted kept calm and followed their coach instructions, meditating and not wasting the few supplies they had is something really incredible. Also, at least as far as I know, there weren’t any conflict between them. Of course, that’s how they should act, but to do this is really hard. Well, imagine you’re trapped with a group and you don’t really know when help will come, your supplies are very limited… I don’t think that it would be easy to be altruistic or even gentle with anyone… To worsen, now imagine that the rescue will be made saving one by one… That boys acted much better than most adult would do, each one of them managed how to properly control their feeling, how to be the masters of their own minds. They all demonstrated characteristics of great leaders!

Hi Ícaro,

I’ve been following BBC podcast as well! The site is quite detailed and there are many reporters. Thank you for your post – I especially agree with being calm at all times and acting as a role model in chaos. It made me think of KEEP CALM AND CARRY ON (maybe the carry on part isn’t applicable in this situation)

It’s great the coach was a monk or else the oxygen levels would have almost depleted in the cave! 15% compared to atmospheric level of 21%, and 9 days without food. That’s really impressive (although BBC claimed that they had food because of someone’s b-day, however this was actually false). Thank god the water that they drank was clear and clean, compared to the murky water with low visibility elsewhere.

The lucky part was that one person was able to speak English, so they were able to effectively communicate with the British Divers who had first found them. Now, everyone across those schools is forced to learn English xD.

I don’t think they had much of a problem being rescued one by one in 3 batches across 3 days. The weakest had to get out first for medical support, and the team was already a very closely bonded group from football. Everyone was so glad there were some teens who in the Wild Boars who didn’t go on the trip, as they had explored the cave before. These teens told the SEALS to check out Pattaya beach, which was extremely close to where the boys were (they left their shoes and some clothes there for tracking).

Indeed, they acted much better than most adults would’ve. However, I think that the reason for this is due to their unselfishness and camaraderie. While firms spend millions of dollars on leadership, teamwork, and teambuilding activities to train their employees, teens often cooperate better without any seminars / workshops. The boys know each other really well, but still, being so mature in that heck of a situation deserves kudos! The rescue workers deserve the most kudos though, as it required so much physical strength (11 hours there and back) to swim in the current, and build basic ropes to not lose sense of direction. Interestingly, the Chiang Rai local government is thinking of making this cave a tourist attraction. Hopefully, they will gain some money back after spending so much on the expedition!

I mildly remember the Chile mine collapse scenario, however that was different to some extent. The miners had already been trained to deal with this situation, and there were emergency food supplies. Although it took around 69 days to get out all the miners, they had some space to move around to exercise and stay healthy (although really deep deep deep down). I believe one of the Chile miners who were rescued sent a video to the trapped Thailand boys giving them hope and optimism :D.

Finally, I’d like to comment on Elon Musk’s case, which was slightly controversial. Some people said he did it for publicity, as some parts of the cave were too small to use the mini submarine. However, it could’ve actually been used in some parts of the cave – just not the extremely narrow ones. After Unsworth called his design a “PR stunt”, Musk got mad and insulted him on social media, which caused a heck lot of attention. Although he gained a lot of publicity, was it a positive or negative image? It really depends on the way you see it. I’m going for positive though (yes I’m slightly naïve aren’t I), as he actually tried a bit to help. Offering help doesn’t always mean others need it, but if everything fails, the SEALS might actually need help from Musk. I think this image is something interesting to talk about. Any arguments :)?

Thanks again,

Harry

Hi Harry!

You really knows a lot about this case! I completely agree with you when you say that the team’s camaraderie was a key part. Even if someone is, normaly, very autruistic, it’s hard to be so unselfish in such a situation. Fear is something hard to control. And yes, of course the abilities os the coach as someone who once was a monk (I don’t know a word for this, maybe ex-monk?) were crucial.

About Musk’s part, I don’t know so much. But well, for everyone in his position, public image is more than just important. So I think that he might want a good repercussion of him by those actions. And how would he get it? By successfully helping in the rescue. So I think that we can afirm that he want to help,

independently of his reasons. But also I think that it’s probable that he also had the true desire of helping. And also it’s not fair to say that he did not have the will of helping and was just pursuing a good image due simply to his “””fail””” in doing it. As I sad, the good image would come only if obtained success, so he would put effort in it either way, and if he “””failed”””, it’s more reasonable tomthink that it was due to some complication and not lack of effort.

Thanks for your attention